Easy Money and Hard Lessons: The [2008-2023] Period Explained

From the ashes of the 2008 financial crisis to the unprecedented challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy has experienced a rollercoaster of events, forever altering the financial landscape. As we witness the recent collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank, it's time to take a step back and examine the key factors and decisions that have shaped our economic trajectory over the past decade and a half.

This blog post examines the impact of these policies and their implications, drawing insights from the 2-hour FRONTLINE documentary "Age of Easy Money" via PBS.

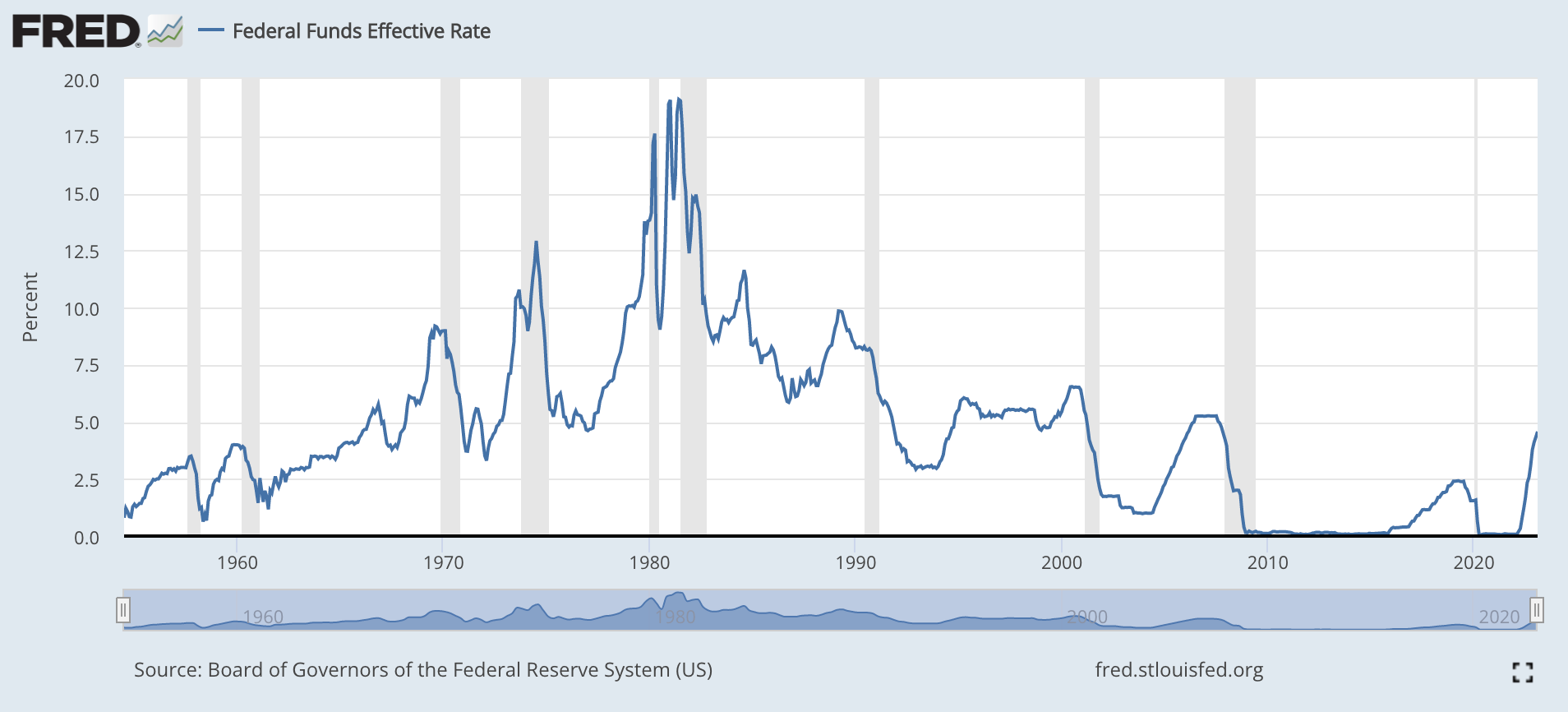

Normally, the Federal Reserve (Fed) is responsible for boosting employment and controlling inflation, mainly by adjusting short-term interest rates. However, the 2008 financial crisis prompted the Fed to adopt unconventional strategies, leading to significant consequences for both the US and the global economy today.

2008 - The Birth of Quantitative Easing:

In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed began lowering interest rates, eventually to almost zero. With traditional tools exhausted, the Fed resorted to "quantitative easing" (or 'QE', a monetary policy action where a central bank purchases predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to stimulate economic activity) - buying 20% of the $5 trillion US bond market to inject $1 trillion into the market. The goal was to give this money to banks, which would then lend to those in need at lower interest rates, ultimately driving up the value of financial assets.

However, the banks began buying the same bonds the Fed was purchasing, making it easier to drive up asset values without lending to households and small businesses. The Fed's role shifted from being a central bank that managed currency to the primary economic engine of America.

Stimulus Packages and the Era of Easy Money [1]:

President Obama: Under his administration, the Federal Reserve implemented three rounds of quantitative easing (QE) between 2008 and 2012 to stimulate the economy during and after the financial crisis, adding approximately $3.6 trillion to its balance sheet.

President Trump: In 2017, Trump made massive tax cuts from 35% to 21% for businesses, further widening the wealth gap. In the same year, he appointed Jerome Powell as the new chairman of the Federal Reserve.

The Problems with Quantitative Easing and Regulatory Failures:

Undermining Democratic Institutions: The small committee controlling the Fed made decisions that could plunge the economy into crisis, making the nation reliant on non-democratic institutions.

Zero Benefits for Savers: QE encouraged risk-taking among borrowers but provided no benefits for savers.

Wealth Inequality: The strategy benefited those who owned the most stocks, further widening the wealth gap.

Corporate Debt: Companies borrowed money to buy back their own stocks, driving up prices and creating a vicious cycle of debt and stock buybacks.

Shadow Banking System: Loosely regulated "shadow banks" (hedge funds and wealth management companies) lobbied the government for their importance, increasing the potential for instability. The government's failure to adequately regulate these entities contributed to this vulnerability.

Incomplete Regulatory Policies: The government's regulatory failures led to vulnerabilities in the market, rather than the Fed's monetary policies alone.

COVID-19 Pandemic and the Fed's Response:

In early 2020, the pandemic caused a shock to the shadow banking system. Everyone wanted cash, leading to a potential collapse of financial markets. The Fed responded with more quantitative easing, buying hundreds of billions of debt from financial institutions. The Trump administration and Congress aimed at helping both Wall Street and individuals & small businesses. The Fed also began buying corporate debt for the first time.

Stimulus Packages and the Era of Easy Money [2]:

President Trump: In early March 2020, the Trump administration and Congress passed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act. By mid-March 2020, the Fed had also made more than $1 trillion available to shadow banks and cut interest rates back down to nearly zero.

President Biden: In March 2021, Biden signed another $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package, adding more money to an already saturated market.

The Consequences of Quantitative Easing and Regulatory Incompetence:

A "No-Lose Casino" Mentality: Aggressive players believed the Fed would bail them out if they failed.

Inflation: Too much money in the market caused inflation to rise as people invested in stocks and cryptocurrencies.

Post-Pandemic Poverty: Between 2021 and 2022, more people struggled to afford food, rent, and utilities than during the pandemic.

The End of Easy Money:

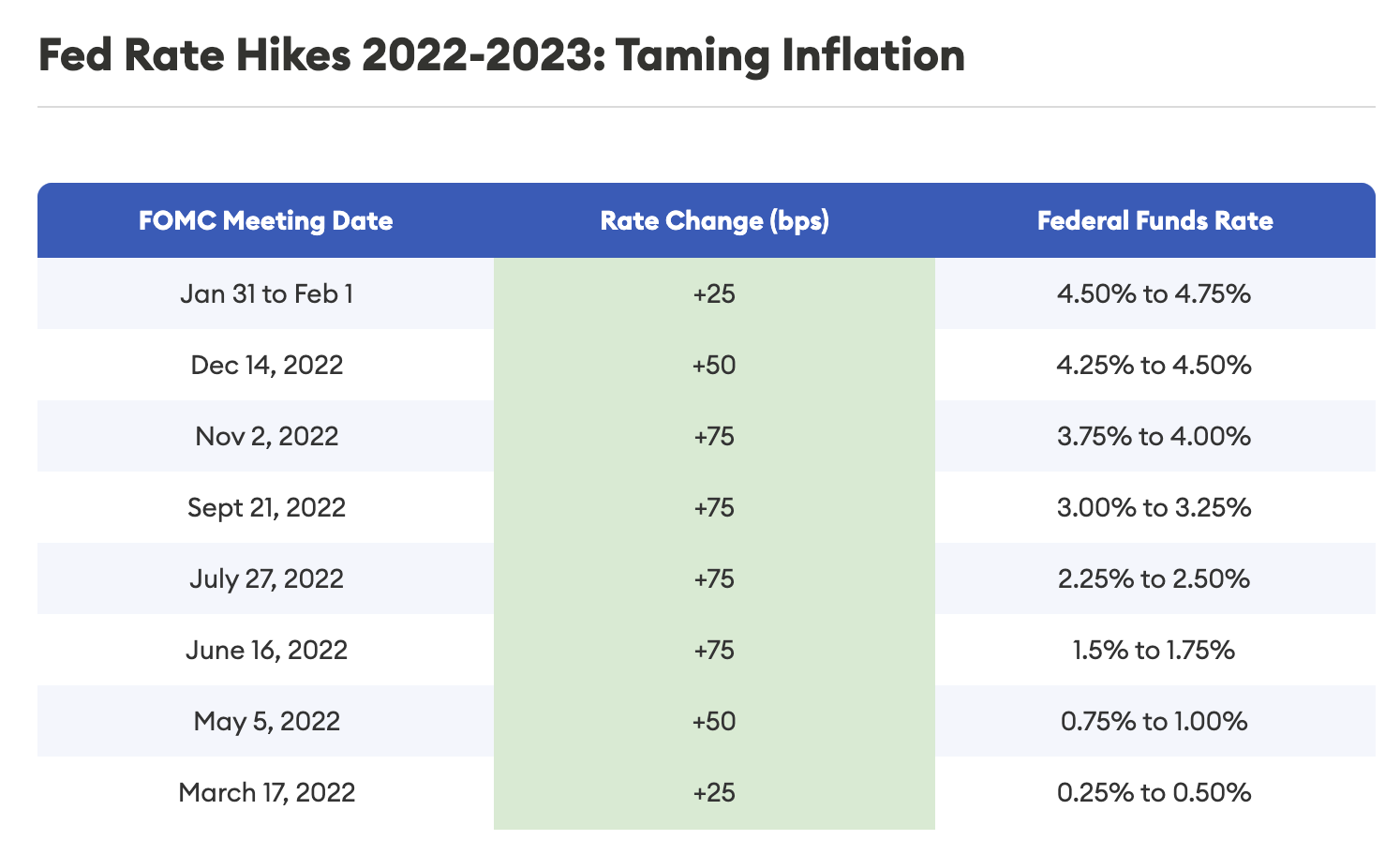

In May 2022, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced the end of quantitative easing and a tightening of interest rates in response to inflation. Within less than a year, from March 2022, the Fed raised the interest rate from 0.25% to 4.75%.

However, this move faced opposition from millions of workers who feared that higher interest rates would make everyday goods, gas, and housing more expensive. In March 2023, the Fed bailed out Silicon Valley Bank, marking the biggest bank collapse since the 2008 financial crisis, suggesting that the interest rate hike might have been too aggressive.

Historically, the Fed has both raised interest rates to nearly 20% to combat double-digit inflation in the early 1980s and dropped them to almost 0% during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic to prevent the financial system from collapsing. As of today, March 21, 2023, the Fed's interest rate stands at 4.75%.

So What's Next?

A good way to predict the next 1-2 years of the economy ahead of us is to look at the Fed's recently announced agenda and whether they are hitting their targets.

As suggested at the beginning of this blog, one of the two primary duties of the Fed is to control inflation. The current annual inflation rate is 6%, a 1% drop from 2021, according to the U.S. Inflation Calculator. However, the Fed aims to reduce it to 2% in the long run, according to the Fed's own FOMC statement made on February 1, 2023.

Considering that the Fed is still 4% away from its inflation rate target and has already experienced the negative consequences of raising interest rates too quickly, I predict that:

the Fed will cautiously increase the interest rate to around 5% - 6% by the end of 2023, further reducing the inflation rate closer to its target. These rate changes will likely be incremental, with increases of 0.25% rather than larger jumps.

What this implies is a slower economy and a weaker stock market performance in the next one or two years compared to the "easy money era." However, these adjustments will pave the way for a healthier and more sustainable economy in the long run.

Thanks to Anna Fu and Arthur Yao for reading drafts of this.