Discovery of Atom

Reading notes from How to Make an Apple Pie from Scratch by Henry Cliff.

Everything is made of atoms.

But what are atoms? What do atoms look like? How did we learn about them?

In this blog, we will explore the history of atom discovery and the interesting stories behind each discovery.

Ancient Times

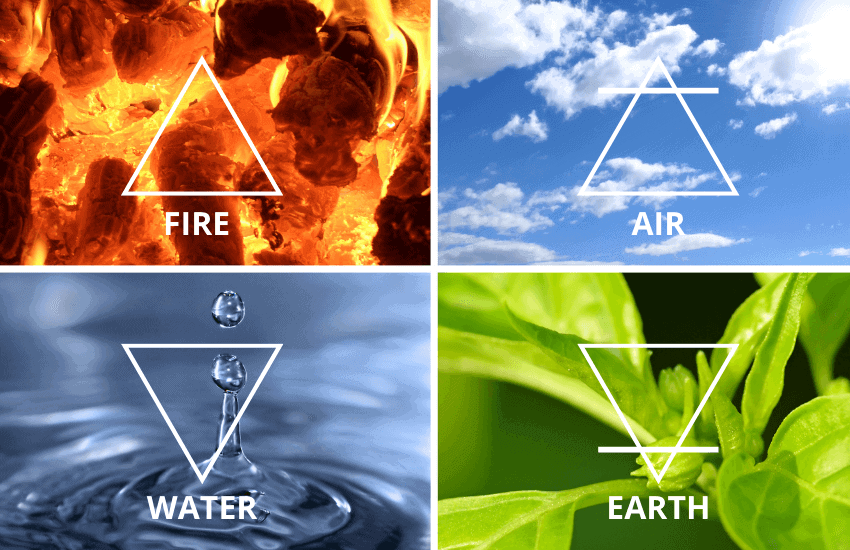

Ancient civilizations (Egypt, India, China, and Tibet) all have different element theories that explain the material world is made up of several basic substances or elements.

The Ancient Greeks argued the material world was made of four materials: earth, water, air, and fire. And they thought that each of the four materials can be transformed into one another.

The 1770s - 1780s: Demolishing the Ancient Theories

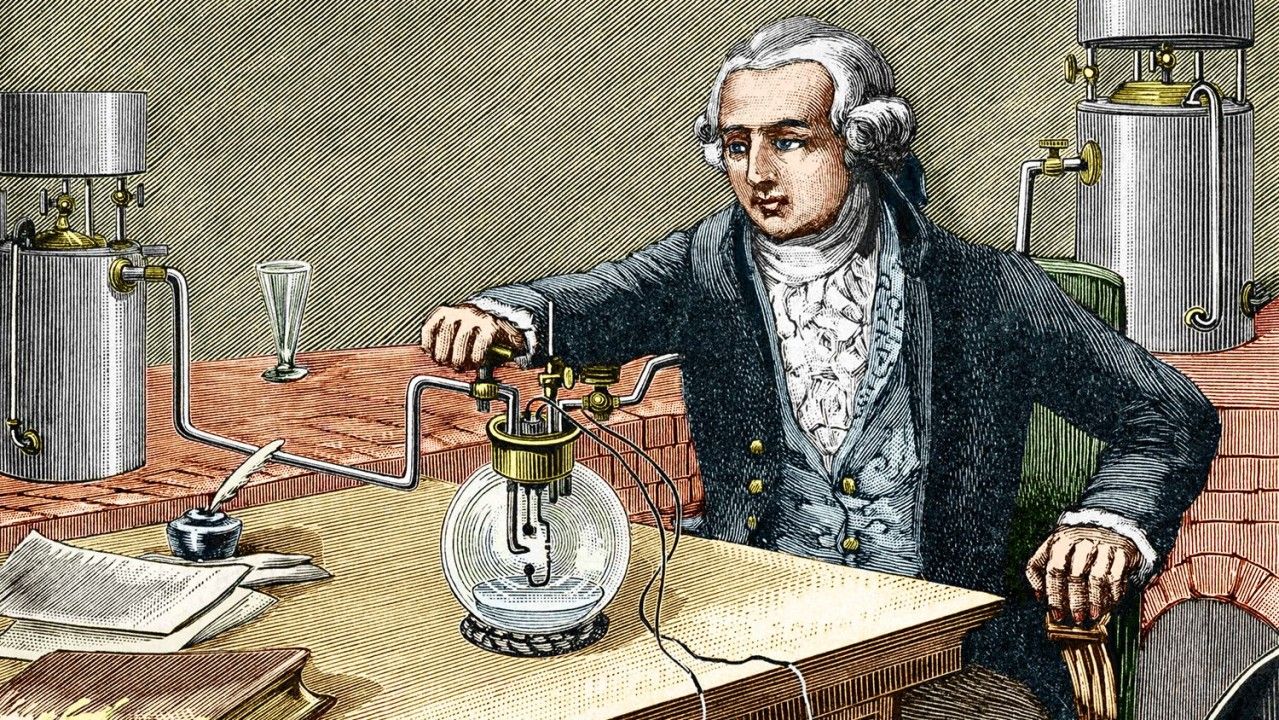

The person who invented modern chemistry was Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. He was a brash, ambitious, and fabulously rich young Frenchman who lived and worked in the second half of the eighteenth century.

What experiments did Lavoisier do to demolish the ancient theories and invent modern chemistry?

(1): The ancient theory of matter raised the prospect of transmuting one substance into another through the practice of alchemy. "Water" was believed to be turned into "earth" after the process of transmutation. Lavoisier attacked this concept of transmutation first:

His experiment was based on a simple assumption: mass is always conserved in a chemical reaction. In other words, the ingredients at the start of an experiment and the products of the experiment should have the same mass.

He weighed the empty glass container before and after the water distillation experiment and found no change in mass. The conclusion was that "water" could not be transformed into "earth", disproving the transmutation from water to earth as stated by the ancients.

Aided by a set of extremely precise and expensive weighing scales, Lavoisier popularized the above assumption when he published the results of his own painstaking experiments in 1773.

That was the law of conservation of mass.

(2): Lavoisier then attacked the most mysterious and powerful element of the four fundamental materials proposed by the ancients: fire.

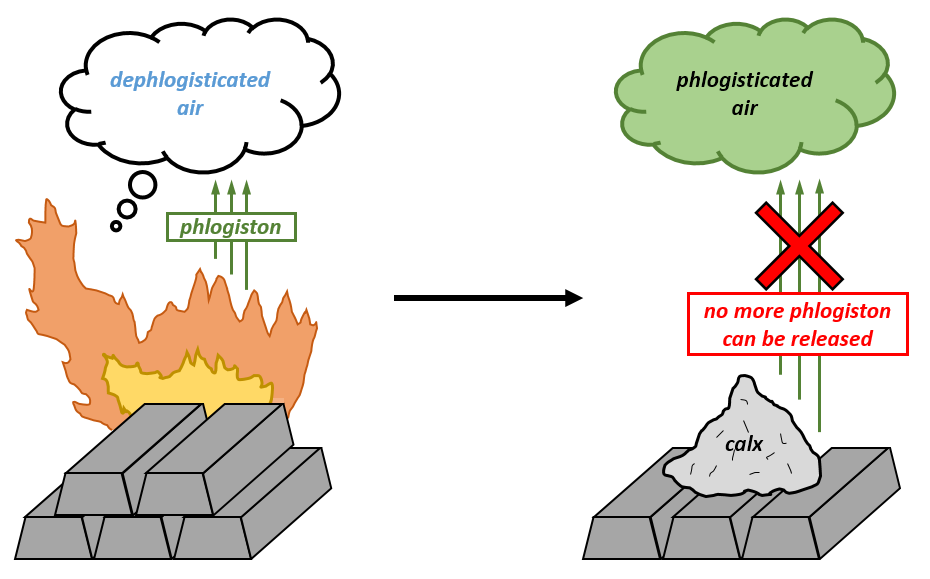

In the mid-eighteenth century, flammable materials like charcoal were believed to contain a substance known as 'phlogiston' that was responsible for the ignition of combust. A fuel like charcoal was believed to have a certain amount of phlogiston in it, which was released during burning, with the burning eventually stopping when all the phlogiston was burned off. Check the first below image.

Unlike the others that believed that burning releases phlogiston, Lavoisier believed that burning involved air being absorbed, which could explain why metals got heavier when burned. But how exactly was it in the air that was consumed in burning?

To prove that fire wasn't an element and phlogiston didn't exist, Lavoisier conducted the experiment on guinea pigs (check the second image below): He placed a guinea pig in an empty bucket surrounded by a container full of ice. The heat from the rodent's body melted to the ice, and by measuring the amount of water that ran out of the bottom of the container he was able to figure out how much heat it was giving off, proving that animals effectively burned their food to create heat.

Lavoisier also proved that water wasn't an element. Instead, water was made from an inflammable air, which he renamed 'hydrogen', and oxygen, which was discovered by the English natural philosopher Joseph Priestley in 1774 and named by Lavoisier.

Then in 1789, he "published Traité élémentaire de Chimie (An Elementary Treatise on Chemistry), the first modern chemistry book that redefined the meaning of a "chemical element" and provided a list of 33 of these new chemical elements, including oxygen, hydrogen, and azote (which we now call nitrogen)".

The 1800s: Imagining Atoms

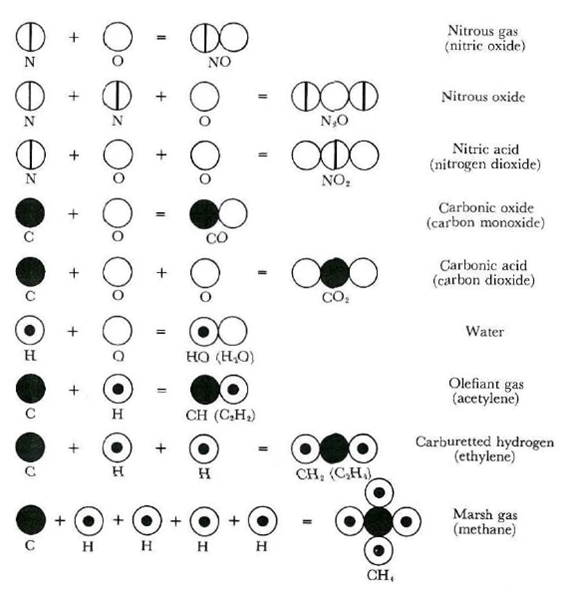

In 1807, John Dalton (a farm boy from Eaglesfield, a small village in the north-west of England) built the bridge between the hidden realm of atoms and the world of chemistry by introducing the atomic theory:

which states that "all matter was made up of solid, indivisible, indestructible atoms, and every chemical element was made of its own unique atom with a definite mass" and that "chemical reactions were nothing more than a process of rearranging these different atoms to make a wider variety of different molecules"

What experiments did Dalton do to recognize atoms?

(1): Initially, Dalton was obsessed with the weather. He wondered why the air feels so heavy with water. He started doing experiments to see how much water vapor a fixed volume of air could absorb.

At the time, people thought that water dissolved in air, like sugar dissolves in a cup of coffee. But Dalton's experiments showed that the container would always absorb the same amount of water vapor regardless of how much air was squeezed into it. He assumed that two atoms of air would interact with each other and two atoms of water vapor would interact with each other as well, but an atom of air and an atom of water vapor don't actually interact with each other.

In 1801, Dalton published his theory of mixed gases, which showed that atoms only repel other atoms of their own kind.

(2): Then, accidentally, Dalton became interested in why certain gases dissolve in water more easily than others. He argued that the weight of the atoms determines how easily they dissolve, with heavier atoms dissolving more easily than light ones. In order to calculate how heavy different atoms were compared to one another, Dalton applied his theory of mixed gases to figure out how many atoms of different chemical elements bind together to make molecules.

His reasoning went something like this: imagine that two atoms of two different chemical elements (say, atom A and atom B) bind together to form a molecule A-B. Now imagine that another atom of A comes along and wants to join the party. Since atoms of A repel each other it will naturally want to get as far away from the other A atom as possible and so attach to the opposite side of the B atom to make a larger molecule A-B-A.

Two different gases made of carbon and oxygen were known in the early nineteenth century: 'carbonic oxide' and 'carbonic acid'.

By weighing the amount of oxygen that reacted with a fixed amount of carbon to make these two gases, Dalton found that carbonic acid contained twice as much oxygen as carbonic oxide. Applying the rules of his atomic theory, carbonic oxide was the simplest molecule, made of one carbon and one oxygen atom (what we now know as carbon monoxide, CO), and carbonic acid contained one carbon and two oxygen atoms (what we now know as carbon dioxide, CO2). Check below image 1.

Finally, Dalton figured out the relative masses of carbon and oxygen atoms, calculating that an oxygen atom weighs about 1.30 times more than a carbon atom.

In 1807, Dalton presented his atomic theory at Edinburgh, and later published his great work, A New System of Chemical Philosophy.

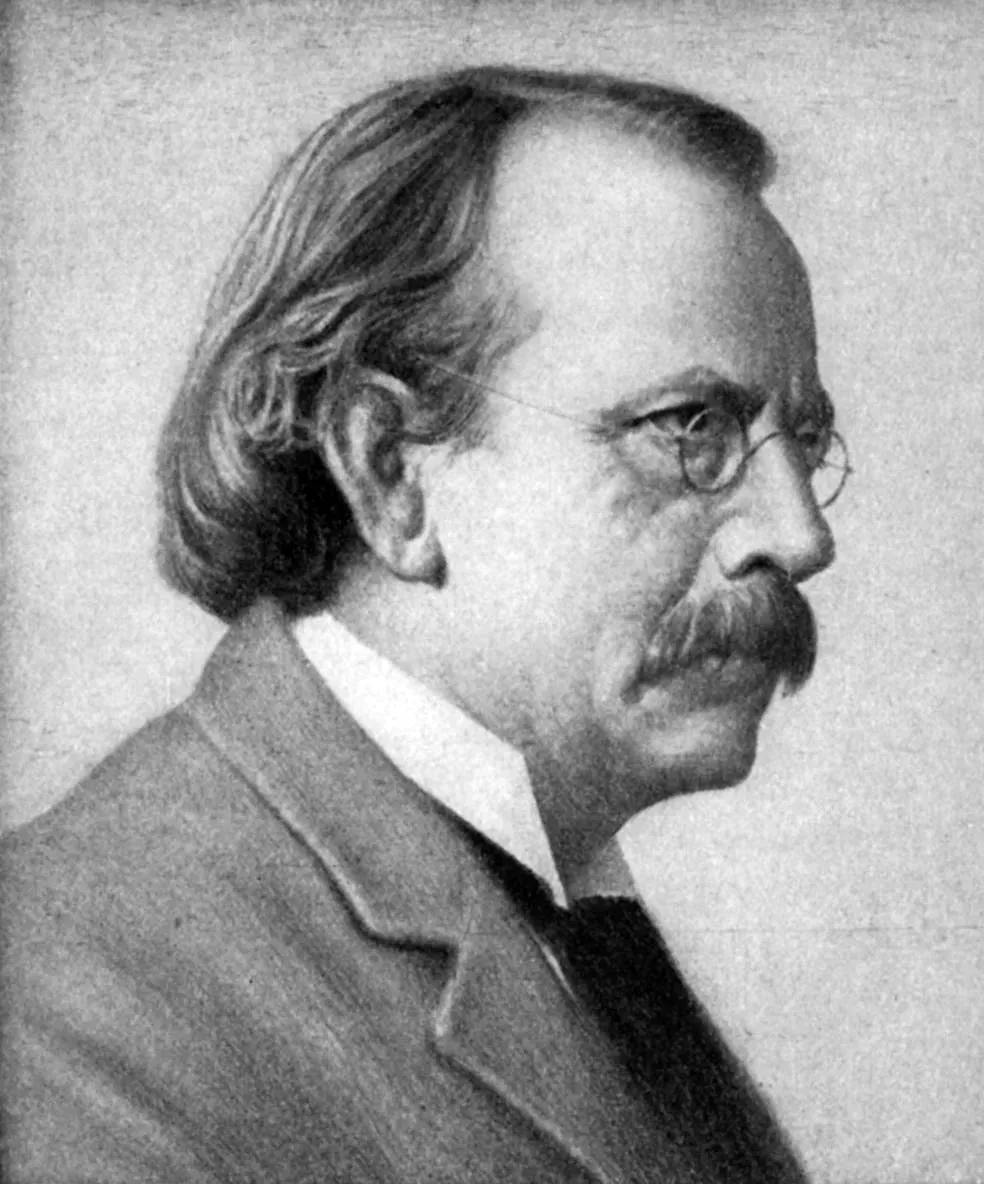

The 1890s: The First Ingredient of the Atom - Electron

In 1897, Joseph John Thomson (or J.J. Thomson) discovered the first ingredient of the atom by discovering that 'corpuscles' (today we call them 'electrons') have mass thousands of times smaller than hydrogen and that the corpuscles were the building blocks of atoms.

What experiment did Thomson do to discover electrons?

It had been known for several decades in the late nineteenth century that when a high voltage was connected to the tube, so-called cathode rays would flow from the negative electrode (the cathode) towards the positive electrode (the anode), creating an eerie green glow where they hit the end of the tube. Check the images below.

Thomson wanted to prove that cathode rays were a flow of negatively charged particles. So he did the following experiment:

(1): He placed the cup at an angle, out of the firing line of the cathode rays. When the tube was switched on, the rays traveled in a straight line, missed the cup, and no negative charge built up.

(2): However, when Thomson used a magnetic field to bend the cathode rays off their straight path and into the cup, a negative charge was detected!

J.J. now needed to know the mass of a cathode ray to prove that cathode rays were negatively charged particles. And the way to do that is to see how the particles curved when they passed through a magnetic field. The heavier the particles were, the less they would bend.

(3): Over the summer of 1897, Thomson and his laboratory assistant Ebenezer Everett worked hard to compare how magnetic and electric fields of different strengths deflected the cathode rays. J.J. compared these cathode rays' mass to their electric charge and had a far more precise measurement of the mass-to-charge ratio.

(4): Finally, their hard work had paid off, showing that Thomson's corpuscles seemed to have mass thousands of times smaller than hydrogen.

The 1900s: Proving the Existence of Atoms

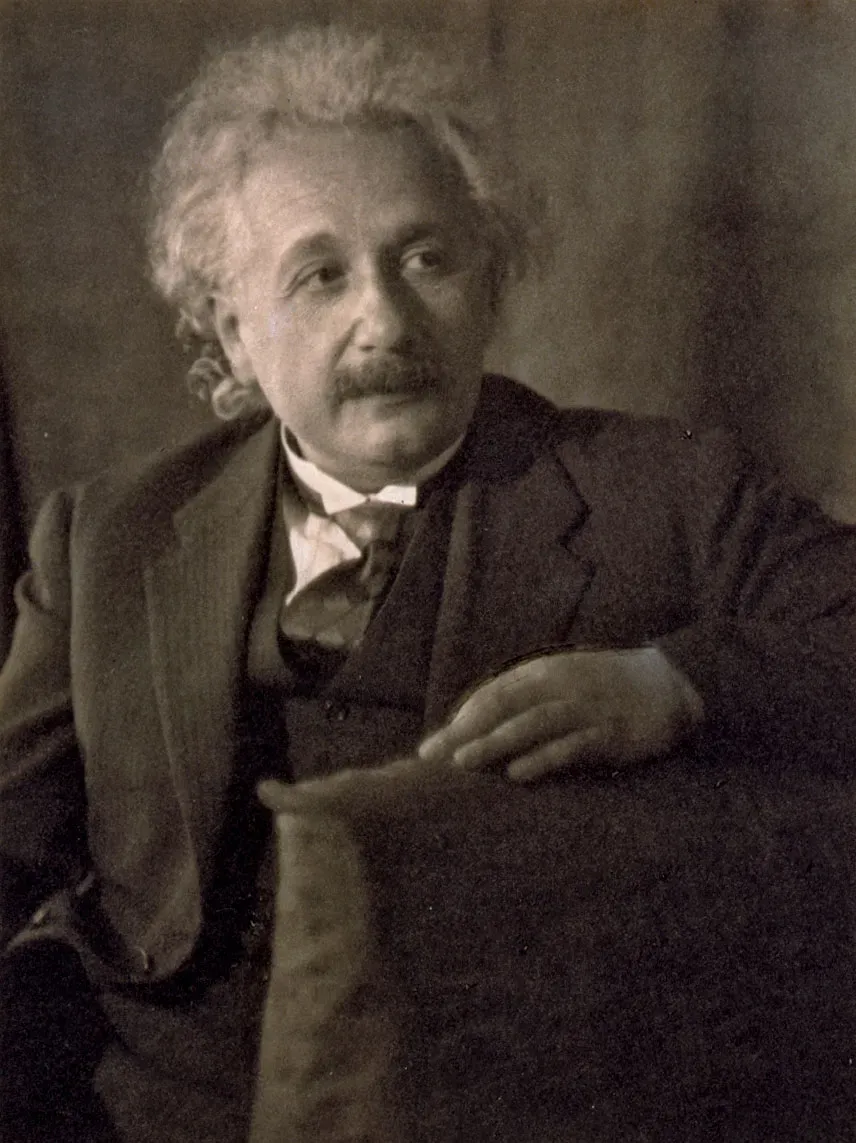

In early 1900s, Albert Einstein, German-born physicist who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, was trying to "settle the big argument: One side said that matter is made of atoms, the other that atoms are just a figment of physicists' imagination and that matter is continuous." [13]

Albert Einstein and Jean Baptiste Perrin proved John Dalton's theory of atoms right by doing the followings:

Albert Einstein published four papers in his 'miraculous year' of 1905, two of which were truly revolutionary (relativity & quantum mechanics). The paper that finally proved the existence of atoms was arguably the least revolutionary of the four:

Robert Brown, a Scottish botanist, discovered a peculiar phenomenon about tiny pollen particles endlessly jiggling around when looking at pollen grains through his microscope in 1827. This was known as 'Brownian motion'. Check below GIF.

If matter is continuous, there are an infinite number of infinitely small water molecules in a drop of water. Then according to Einstein's equation (the distance a pollen particle jiggles away from its starting point in some amount of time goes up as the number of water molecules goes down), a pollen particle wouldn't move at all. "If the number of water molecules is effectively infinite then there will always be an equal number pushing on the pollen particle from any given direction, which means that the forces experienced by the particle are always perfectly balanced and hence the pollen particles stays dead still."

But pollen particles do move! Einstein showed that the Brownian motion only made sense if atoms were real. But he needed more experimental proof that "the way small particles wander about in the water corresponds precisely to his equation".

Jean Baptiste Perrin (French Physicist) and his team of research students performed a series of experiments that verified Einstein's predictions:

proving that atoms existed through calculating the number of water molecules in a drop of water based on how far a pollen particle wanders in a given amount of time) were correct in between 1908 and 1911

The combined effort of Einstein's theories and Perrin's experiments proved John Dalton's atom theory right.

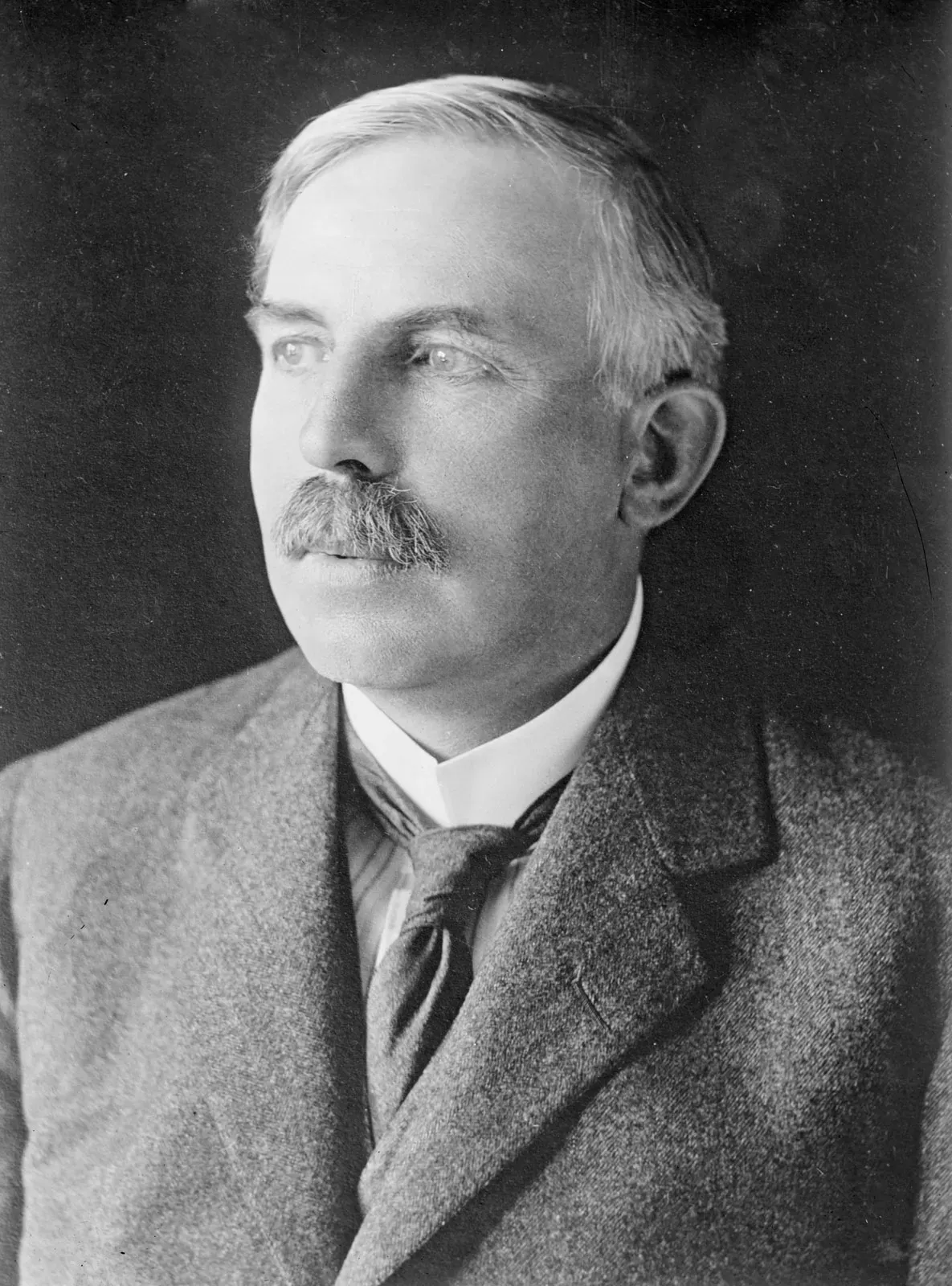

The 1910s: The Heart of the Atom - Nucleus

Ernest Rutherford, J.J. Thomson's student at the Cavendish Laboratory (and a farmer's son from Pungarehu on New Zealand's North Island), went to Britain in 1985 and changed how we think about atoms forever by:

discovering that there were two types of radiation being shot out by uranium: (1) one that only flew a few centimeters through the air before stopping, and (2) a second more penetrating ray that could travel much farther and even pass through strips of metal. He named them alpha and beta rays.

then proving that alpha particles were helium atoms that had lost two electrons

discovering the atomic nucleus in 1910

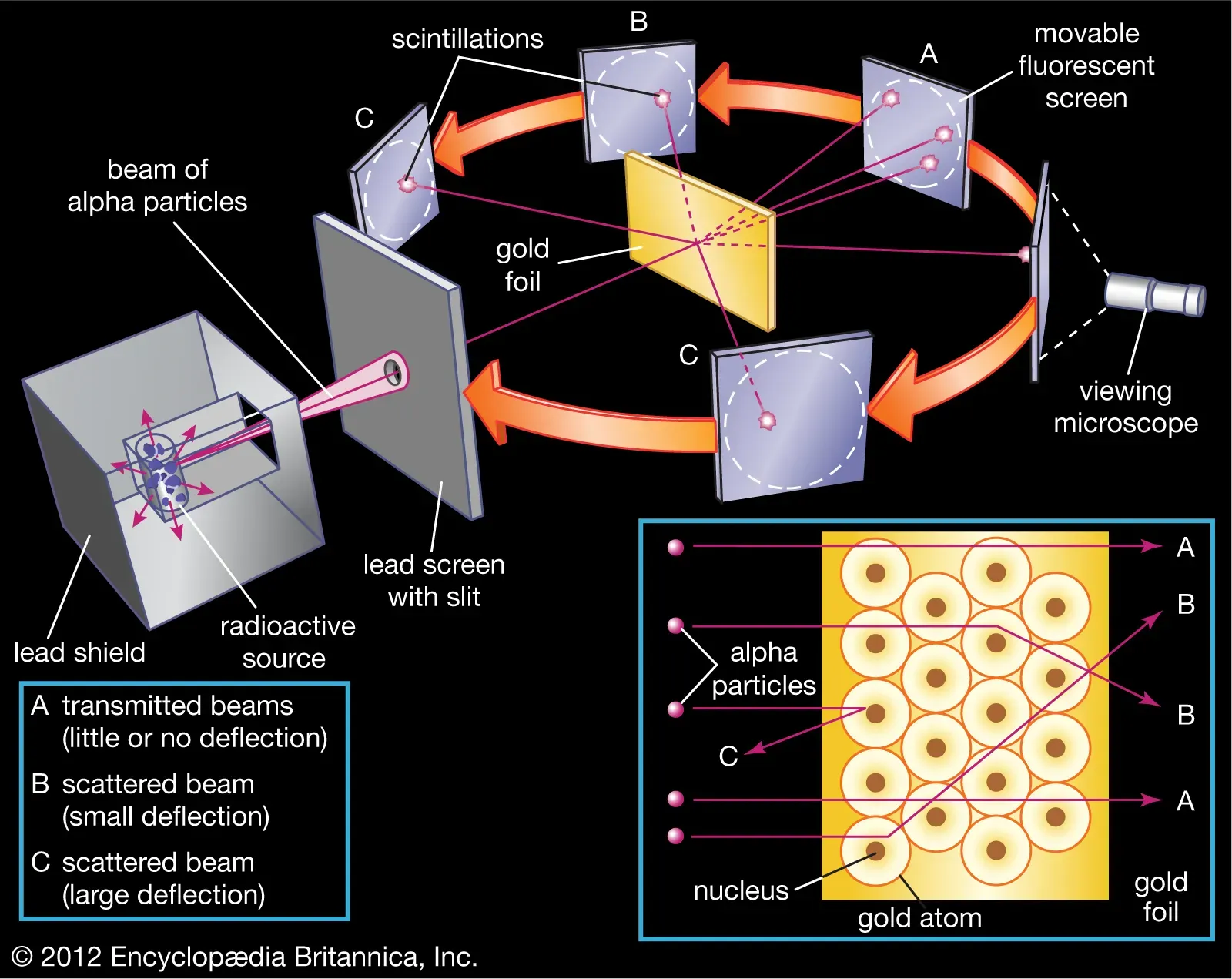

What experiment did Rutherford and his team do to discover the nucleus of an atom?

(1) Rutherford was puzzled when he observed that "the alpha particles were being knocked off course by collisions with the gas molecules". But "how could projectiles of such 'exceptional violence' (alpha particles got shot out of disintegrating atoms at incredibly high speeds) be deflected by something as insubstantial as a gas molecule?"

(2) Ernest Marsden was one of the new students of Rutherford. He conducted experiments to see "if any alpha particles bounced backwards off the gold foil." After three days of eye-straining work, he shocked his mentor by showing the result that "the alpha particles were being knocked backwards!" Check below image 1-3 for reference. This was "as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell a t apiece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you."

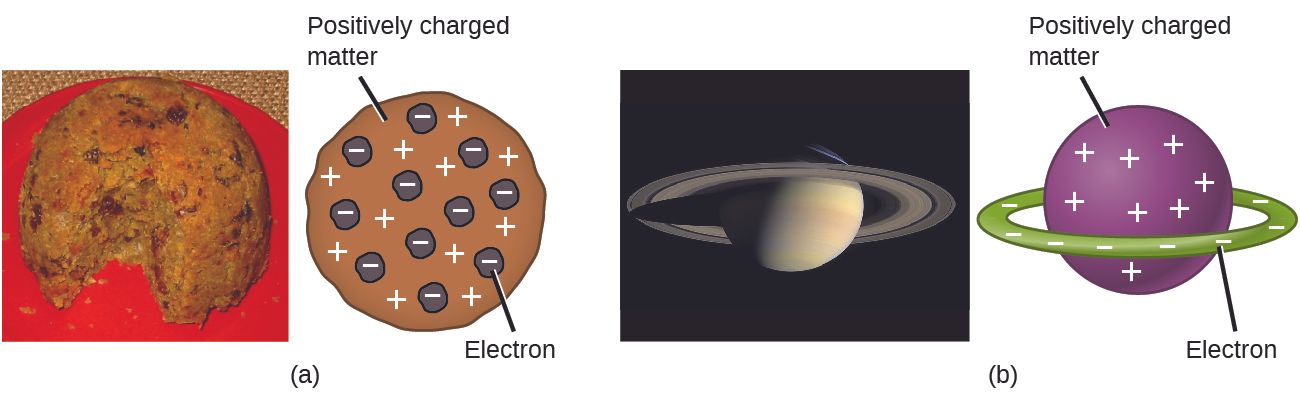

(3) In December 1910, Rutherford disproved his old mentor J.J.'s pudding-like atom structure. Instead, it was "a tiny solar system, with negatively charged electrons held in orbit around an infinitesimal positively charged sun." Check figure (a) and figure (b) as shown in image 4 as well as image 5 below.

"But Rutherford's atom had a big problem: he assumed that every atom is like a tiny solar system with electrons circulating around the nucleus. But this would make every atom unstable because this implied that the electrons should be constantly emitting light, losing a bit more energy with each orbit, until they eventually spiraled into the nucleus."

Niels Bohr, a brilliant young Danish physicist whose theory led to a revolutionary new description of the subatomic world called "quantum mechanics", helped solve Rutherford's problem by:

arguing that electrons could only move around the nucleus in certain fixed orbits, emitting quanta of light (inspired by Albert Einstein and Max Planck) as they jumped from one level to another

Henry Moseley, a research student working under Rutherford in the Manchester lab, discovered something profound after Rutherford published his first paper on the nuclear atom:

In 1913, he discovered that the atomic number, which was shown on the periodic table cerated by Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev in 1869, was the number of positive charges in the atomic nucleus.

The 1930s: Neutrons

It was hard to prove the existence of neutrons because every method of detecting particles that exists at the time relies on the particles(such as protons and electrons)' electric charge to make them visible, which is something that neutrons don't have.

Irène Curie, the daughter of Nobel Prize winners Pierre and Mari Curie (who discovered two radioactive elements 'radium' and 'polonium' back in 1898), and her husband Jean-Frédéric Joliot helped prove the existence of neutrons by discovering that when gamma rays "were fired at paraffin wax, protons came whizzing out at tremendous speeds."

In 1932, after eleven years of struggle, James Chadwick (the assistant director of Cavendish Laboratory under his director Ernest Rutherford) discovered the final and most elusive building block of the atom, the neutron, by:

getting inspiration from the work of Irène Curie and her husband Frédéric

assuming the radiation given off by beryllium was made of neutrons instead of gamma rays (unlike what Irène and Frédéric had suggested in their research)

proving his assumption correct with his own experiments (check images below)

but he failed to calculate the mass of neutrons correctly

Back in Paris, Irène and Frédéric continued their research on beryllium and used a more precise calculation method to show that the mass of the neutron is actually about 0.1 per cent more than a proton, instead of it being slightly lighter than a proton as suggested by Chadwick.

In fact, Rutherford's idea of the nucleus being made of protons and electrons was completely wrong:

Electrons are actually created at the moment a nucleus undergoes radioactive decay.

The atomic nucleus is made not of protons and electrons, but of protons and neutrons.

During radioactive beta decay, a neutron in the atomic nucleus transforms into a positively charged proton, which stays inside the nucleus and shoots out a negatively charged electron.

After over 1.5 centuries of hard work from generations of brilliant scientists, we finally know that [electrons, protons, and neutrons] make up all atoms. But how do these three types of particles come together? We shall find out in the next blog post of our Atom Series.

Sources

[0]: Cliff, Harry. How to Make an Apple Pie from Scratch: In Search of the Recipe for Our Universe, from the Origins of Atoms to the Big Bang. Picador, 2021.

[1]: Four Elements – What Do They Symbolize? (Spiritual Meaning)

[2]: Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier: The Father of Modern Chemistry who was Guillotined...then Exonerated

[3]: Oxygen's Alchemical Origins: The Phlogiston Story

[4]: The Father of Modern Chemistry Proved Respiration Occurred by Freezing a Guinea Pig

[6]: A level Chemistry Revision: Physical Chemistry - Atomic Structure

[7]: The Scientific Odyssey Episode 2.6.1: Supplemental - John Dalton

[8]: Wikimedia Commons: A New System of Chemical Philosophy

[9]: Australia’s most powerful electron microscope is the “ultimate nanotechnology tool”

[10]: Britannica: J.J. Thomson

[11]: Cathode Ray Tube Experiments

[12]: Evolution of Atomic Theory

[13]: From graduation to the “miracle year” of scientific theories of Albert Einstein

[14]: Wikimedia Commons: File:Brownian motion 5particles 150frame

[15]: Pollen Grains in Water - Brownian Motion

[16]: Britannica: Ernest Rutherford

[18]: Linda Hall Library - HENRY MOSELEY

[19]: Britannica: Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie

[20]: Khan Academy: Discovery of the electron and nucleus