Seven Brief Lessons on Physics (Carlo Rovelli)

In this book summary, I will explore the main ideas expressed in the book Seven Brief Lessons on Physics by Carlo Rovelli, an Italian theoretical physicist.

Lesson 1

[The Most Beautiful of Theories]

Albert Einstein's moment of enlightenment came when he realized that space and gravitational field are the same thing. This later evolved into the Theory of General Relativity (Rovelli, 10). Prior, our entire view of the universe was based on the founding father of physics Isaac Newton; That is, space is one huge container box, and within this box, there is a gravitational force being exerted between objects (Rovelli, 5). Einstein's theory also tells us that planets orbit around the sun and things fall because of space curves. Even more surprisingly, time curves as well.

But this is not all. The theory suggests that space can expand and contract, which was validated by astronomical observations that showed clear evidence that our universe is expanding and, therefore, it is logical to assume that there is a starting point of this expansion, which led to the 'Big Bang' moment discovery.

Furthermore, the theory shows that space actually moves like the surface of the sea (Rovelli, 9). And these ripples in space are called gravitational waves.

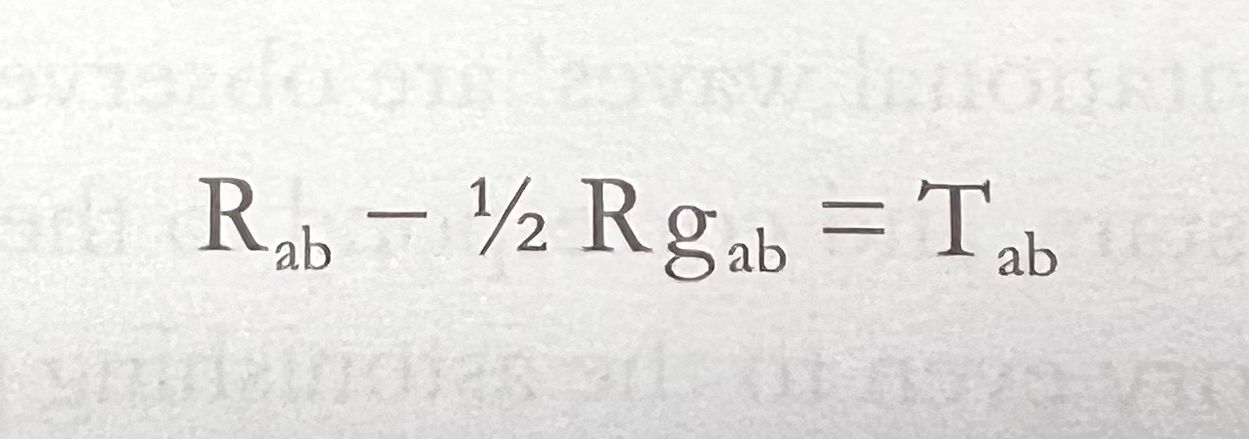

And all the fantastic wonders discussed above are included in one simple, elegant mathematical equation:

Lesson 2

[Quanta]

Alongside general relativity, quantum mechanics is the other one of the two twentieth-century physics pillars, which was "born" in 1900. Without the quantum theory, there will be no transistors that make up the chips inside of the electronic device that you're using to read this blog right now.

And in the first decade of the twentieth century, it was Einstein again that "gave the real birth certificate" of the quantum theory through his article showing that light is made of 'packets of energy', or 'particles of light', called 'photons': "The energy of a light ray spreading out from a point source is not continuously distributed over an increasing space but consists of a finite number of 'energy quanta' which are localized at points in space, which move without dividing, and which can only be produced and absorbed as complete units." (Rovelli, 13).

In the second and third decade of the twentieth century, Dane Niels Bohr brought the theory further by creating the term 'quantum leap', which describes the movement of electrons 'jumping' between one atomic orbit and another with fixed energies, emitting or absorbing a photon when they jump (Rovelli, 14).

Then the young German genius Werner Heisenberg argued that "electrons only exist when they are interacting with something else" (Rovelli, 15). This led to the discovery that "it is not possible to predict where an electron will reappear, but only to calculate the probability that it will pop up here or there" (Rovelli, 16).

But a century after the birth of quantum mechanics, we still don't understand its full picture.

Lesson 3

[The Architecture of the Cosmos]

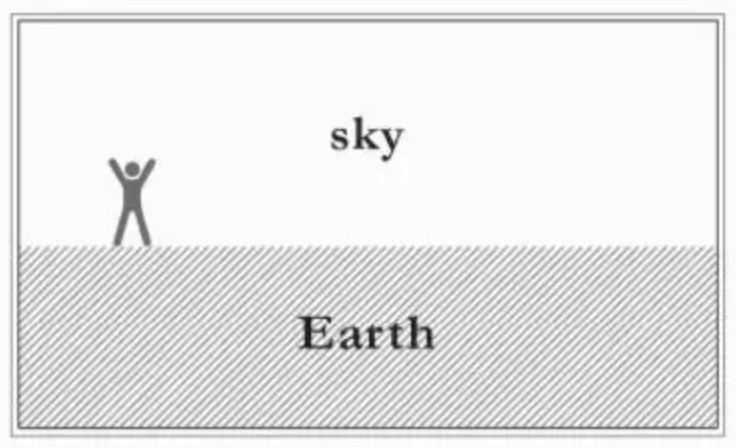

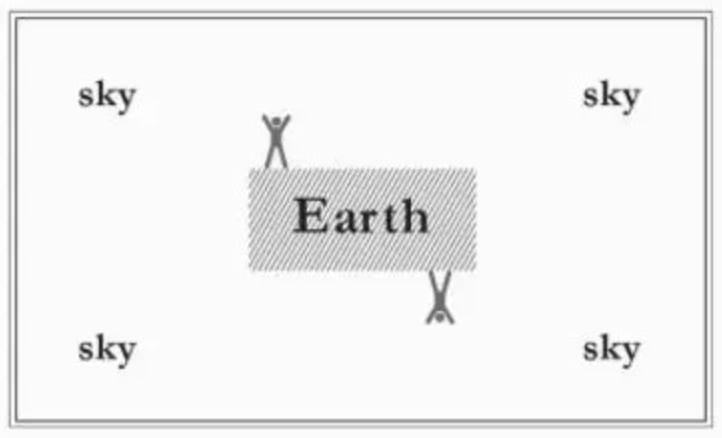

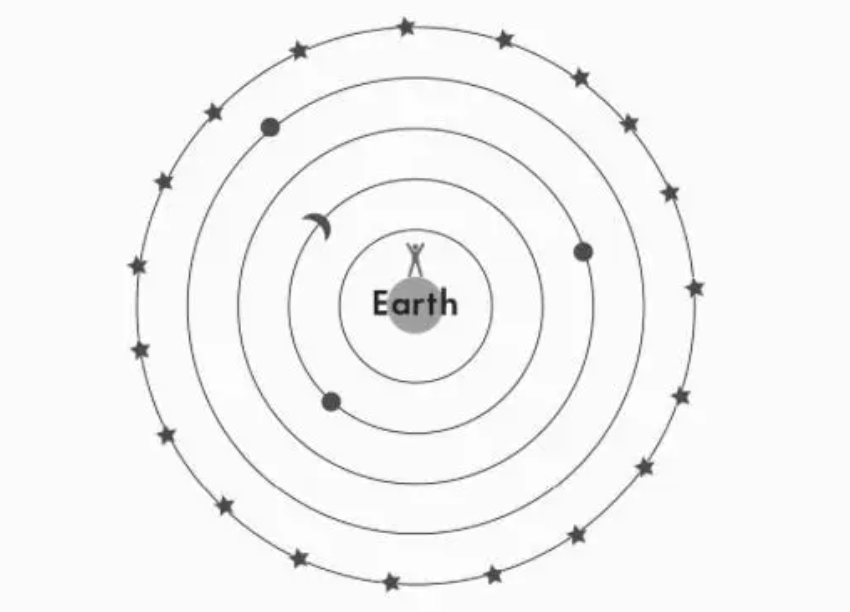

Over the course of a few thousand years of human history, we've changed our view of the world from seeing only the earth and the sky (image 1) to realizing that the world is not flat (image 2),

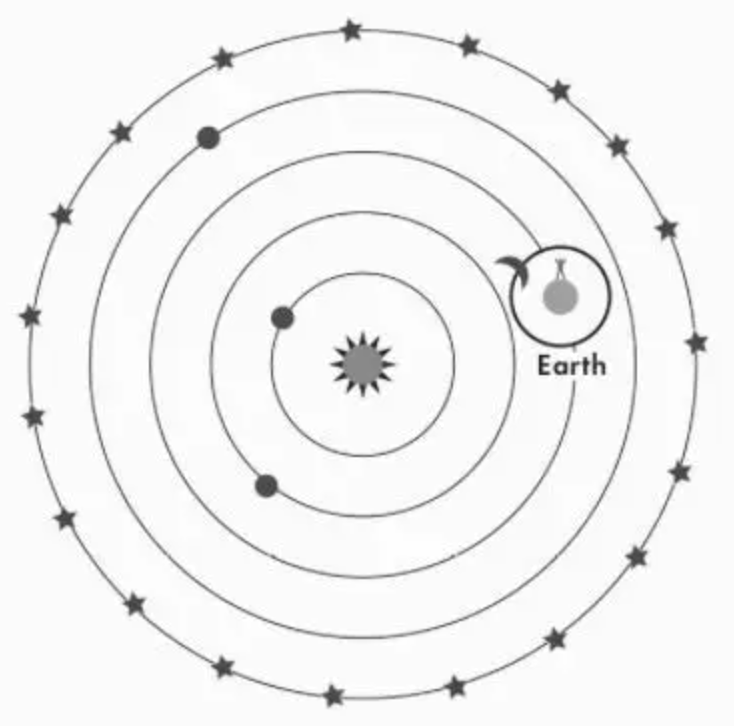

to recognizing the spherical nature of our planet and that we are surrounded by stars (image 3),

to acknowledging that the sun is actually the center and that earth is just orbiting around it (image 4),

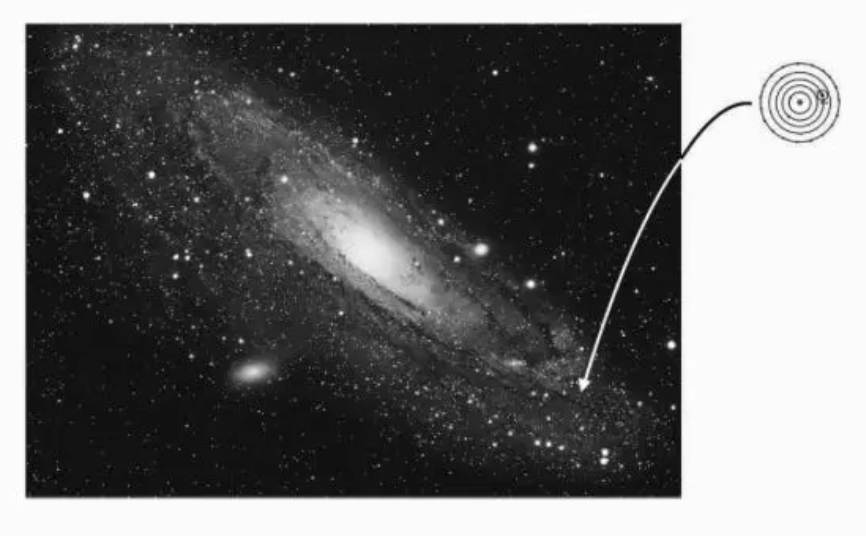

to know that the sun is just another star like others and our solar system is just one of the vast number of other galaxies (image 5),

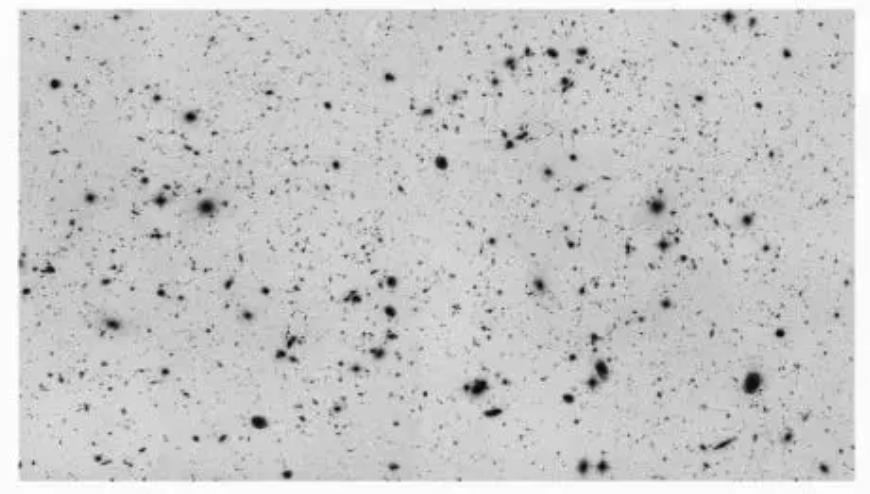

to observing different galaxies through telescopes and learning that there are actually a hundred billion suns similar to ours inside each of the black dots (or galaxies) shown in image 6,

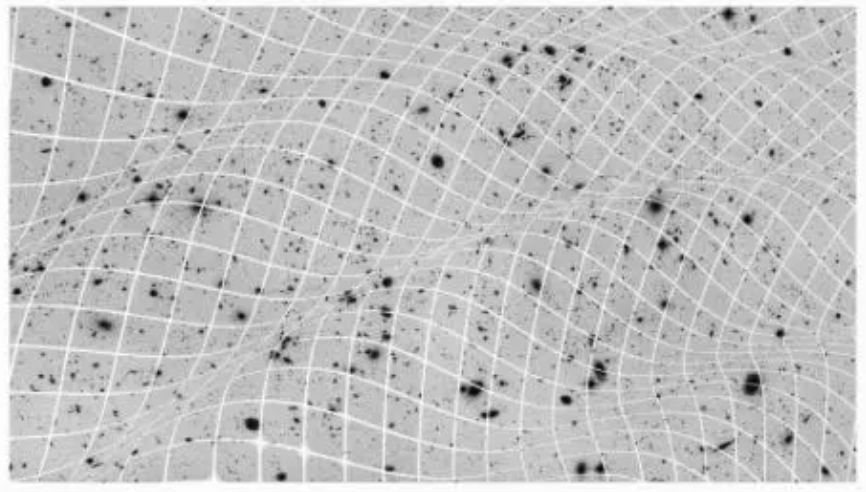

then to discovering that our universe is furrowed by great waves with splashes of galaxies being moved by waves similar to those of our ocean (image 7).

And finally, our current image of the universe is that it started as a tiny ball and exploded and expanded to its present cosmic dimensions as shown in image 8 (Rovelli, 28).

Lesson 4

[Particles]

With great physicists such as Richard Feynman and Gell-Mann building and improving the details of particle theory from the 1950s to 1970s, Paul Dirac was able to come up with the first and principal equations of the Standard Model of elementary particles, the best theory by far that we have ever invented to accurately describe the world we see. And this is what we currently know of the matter:

"A handful of types of elementary particles, which vibrate and fluctuate constantly between existence and non-existence and swarm in space even when it seems that there is nothing there, combine together to infinity like the letters of a cosmic alphabet to tell the immense history of galaxies, of the innumerable stars, of sunlight, of mountains, woods and fields of grain, of the smiling faces of the young at parties, and of the night sky studded with stars" (Rovelli, 35 - 36).

However, the Standard Model also has its limitations. For instance, it fails to describe the large clouds of material surrounding every galaxy that "cannot be seen directly and we do not know what it is made of" (Rovelli, 33). And nowadays we call this invisible thing 'dark matter'. But we still don't understand what it really is.

Lesson 5

[Grains of Space]

Despite being the two greatest theories of the twentieth century, general relativity(that helped develop the study of cosmology, gravitational waves, black holes, etc.) and quantum mechanics(that helped develop the study of atomic physics, nuclear physics, the physics of elementary particles, etc.) are contradictory to each other (Rovelli, 37). The first suggests that "the world is curved space where everything is continuous", while the second says that "the world is a flat space where quanta of energy leap" (Rovelli, 38). Therefore, while being very successful theories, they cannot both be right at the same time.

But this dilemma is actually appreciated by the physics community because it represents a very good opportunity for physicists to come up with a new coherent theory when there are contradictions between successful theories. History has shown us that: "Newton discovered universal gravity by combining Galileo's parabolas with the ellipses of Kepler. Maxwell found the equations of electromagnetism by combining the theories of electricity and of magnetism. Einstein discovered relativity by way of resolving an apparent conflict between electromagnetism and mechanics" (Rovelli, 39).

In the twenty-first century, a group of theoretical physicists is trying to bridge the gap between the two theories by proposing the "loop quantum gravity" theory, which describes the world like this: "There is no longer space which 'contains' the world, and there is no longer time 'in which' events occur. There are only elementary processes wherein quanta of space (atoms of space) and matter continually interact with each other. The illusion of space and time which continues around is is a blurred vision of this swarming of elementary processes." (Rovelli, 40-42).

One of the ways to verify this bold statement is through the study of black holes that are formed by collapsed stars. The formation of these black holes begins with the matter of collapsed stars being crushed by their own weight and eventually collapsing upon themselves (Rovelli, 44). Once this 'Plank star' compressed to the maximum it rebounds and begins to expand again (Rovelli, 45). In short, a black hole is "a rebounding star seen in extreme slow motion" (Rovelli, 45).

The loop quantum gravity theory also infers the origins of the universe from a completely new perspective: what we previously described as the 'Big Bang' explosion event may have actually been a 'Big Bounce' --- "Our world may have actually been born from a preceding universe which contracted under its own weight until it was squeezed into a tiny space before bouncing out and beginning to re-expand, thus becoming the expanding universe which we observe around us." (Rovell, 46).

Therefore, our new image of the universe is transformed into this:

Lesson 6

[Probability, Time and the Heat of Black Holes]

Why does heat pass from hot things to cold things and not the other way around?

According to Boltzmann, it is sheer chance: "The probability that when molecules collide heat passes from the hotter bodies to those which are colder can be calculated, and turns out to be much greater than the probability of heat moving toward the hotter body." (Rovelli, 54).

During the twentieth century, our study of the science of heat (or 'thermodynamics') and the science of the probability of different motions (or 'statistical mechanics') have been extended to electromagnetic and quantum phenomena, which emphasizes the concept of the gravitational field (Rovelli, 55).

So what is the gravitational field?

It is space itself, in effect space-time (Rovelli, 56). When heat is diffused to the gravitational field, time and space must vibrate (Rovelli, 56).

But what is a vibrating time? We don't know yet. To answer this, we first have to ask ourselves a more fundamental question: 'what exactly is the flow of time'? Does our concept of past, present, and future objectively exist?

According to the author, the way to figure it out is to look at the connection between time and heat (Rovelli, 60). He thinks that there is a detectable difference between the past and the future only when there is the flow of heat: "Heat is linked to probability; and probability in turn is linked to the fact that our interactions with the rest of the world do not register the fine details of reality. The flow of time emerges thus from physics... in the context of statistics and of thermodynamics." (Rovelli, 60).

Stephen Hawking provided a small clue through his calculation, which demonstrated that black holes are always 'hot' using quantum mechanics (Rovelli, 61). And that heat of black holes is quantum effect upon an object (the black hole), which is gravitational in nature (Rovelli, 62). But we have not yet deciphered the true nature of time, which sits at the intersection point of gravity, quantum mechanics, and thermodynamics (Rovelli, 62).

In Closing

[Ourselves]

What are human beings? Who are you? Do we really exist?

The author thinks that 'we', human beings, are observers of the world that are also "nodes in a network of exchanges through which we pass images, tools, information and knowledge" (Rovelli, 64). The primal substance of our thoughts is "an extremely rich gathering of information that's accumulated, exchanged, and continually elaborated" (Rovelli, 68).

But we're not external observers. Instead, we are an integral part of the world that we perceive (Rovelli, 64). And this world that we are a part of is run on the laws of nature.

But this raises the question of whether we are actually 'free' to make decisions if our behavior "does nothing but follow the predetermined laws of nature" (Rovelli, 70).

Sadly, there is nothing about us that can escape the norms of nature (Rovelli, 70). However, being determined by the laws of nature doesn't mean that we are not free: "Our free decisions are freely determined by the results of the rich and fleeting interactions between the billion neurons in our brain: they are free to the extent that the interaction of these neurons allows and determines." (Rovelli, 71).

In short, each individual is a complex, tightly integrated process (Rovelli, 72).

Nature is our home, and in nature we are at home. This strange, multicoloured and astonishing world which we explore - where space is granular, time does not exists, and things are nowhere - is not something that estranges us from our true selves, for this is only what out natural curiosity reveals to us about the place of our dwelling. About the stuff of which we ourselves are made. We are made of the same stardust of which all things are made, and when we are immersed in suffering or when we are experiencing intense joy we are being nother other than what we can't help but be: a part of our world. (Rovelli, 77 - 78)

Thanks to Nathan Magers, Jan-Michael Marshall, and Kelvin Mo for reading drafts of this piece.