The Power Law (Sebastian Mallaby)

Venture capital (VC) has become a buzzword in the worlds of finance and startup, attracting investors looking to make big returns by betting on the next big thing. But how did this industry come to be? The history of venture capital is a story of innovation, risk-taking, and big rewards. In this blog, we will explore the evolution of venture capital and how different approaches have emerged over the decades, shaping the industry and the world we know today.

The 1950s: The Birth of Venture Capital

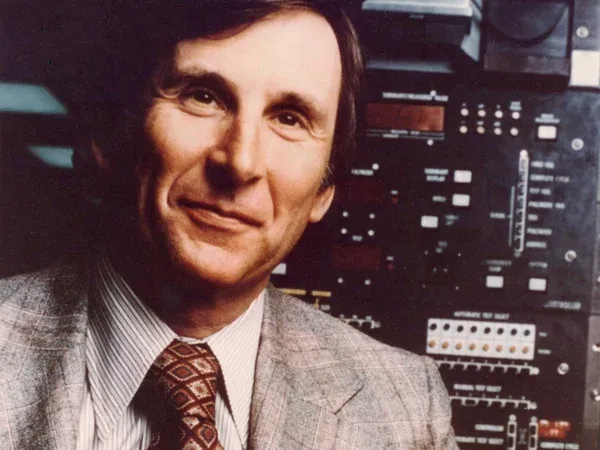

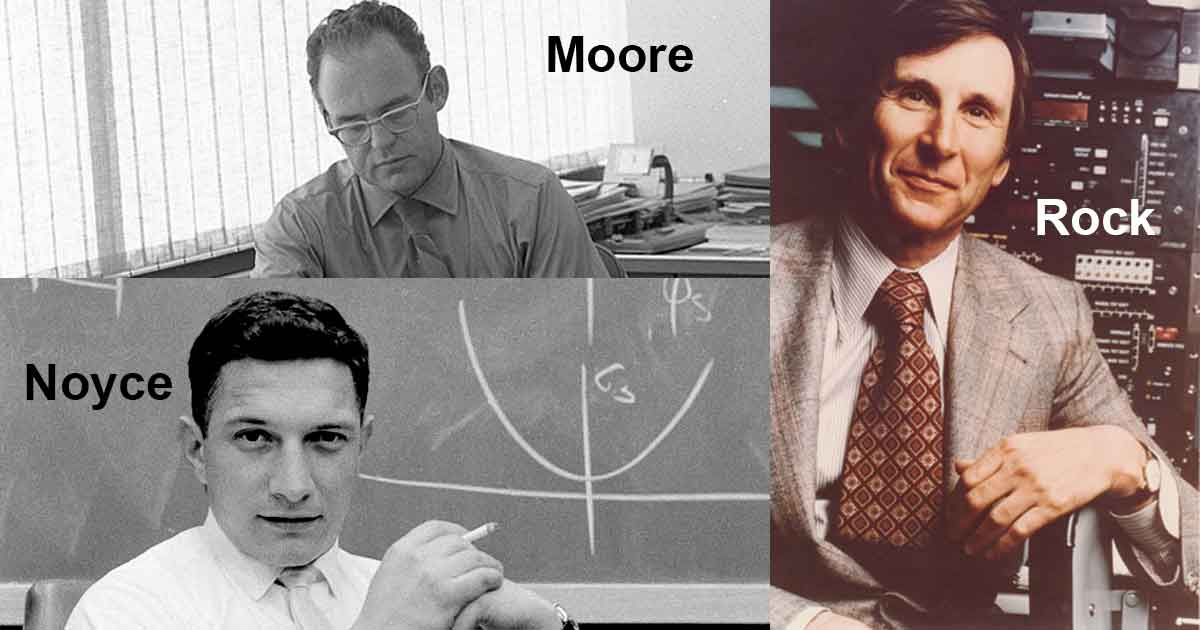

Arthur Rock is considered the "founding father" of venture capital. After graduating from Syracuse University with a bachelor's degree in business administration and from Harvard University with an M.B.A., he began working as an investment banking analyst in New York in 1951.

At the time, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory was a leading player in the emerging field of semiconductor technology, but its founder, William Shockley, was both a brilliant Nobel Prize-winning scientist and an absolute jerk to work with. Soon, a group of eight engineers at the lab, unable to handle Shockley's fiery temper, decided to leave the company to look for other job opportunities.

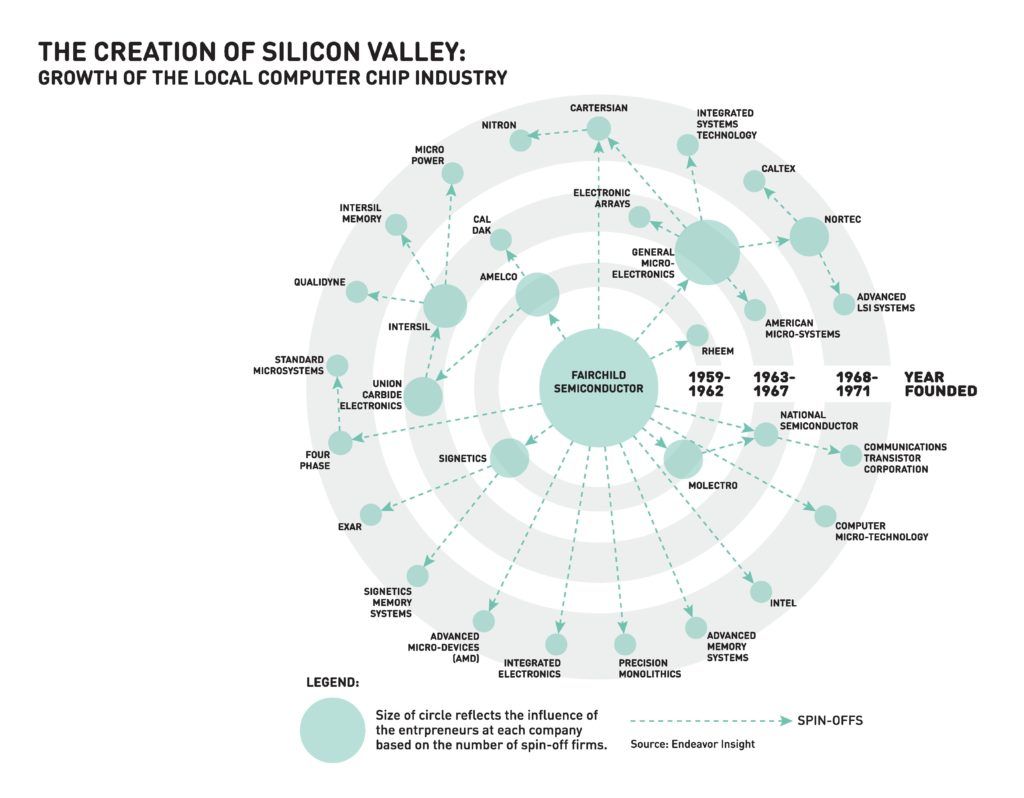

In 1957, Rock's financing story of Fairchild Semiconductor represented the beginning of liberating laborers with capital (Mallaby, 33-39):

Rock saw the potential in the "traitorous eight" and offered to help them secure funding for their new venture. After getting rejected by 35 potential investors, he arranged for them to meet with Sherman Fairchild (a playboy with an inherited fortune) who agreed to provide initial funding for the new company, which became known as Fairchild Semiconductor. But the Fairchild investment "came in the form of a loan rather than equity" and "it came bundled with an option to purchase all of the new company's stock for $3 million".

Before Rock's involvement, scientists and engineers like the "traitorous eight" at Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory had almost no opportunity to start their own companies or own shares in them.

For the first time in human history, Rock started liberating laborers with capital.

In 1959, 2 years after the founding of Fairchild Semiconductor, Ferman Fairchild decided to execute his special loan agreement and bought the entire company from the traitorous eight for $3 million, with each of the Traitorous Eight founders receiving $300,000, a 600x return from their initial $500 startup investment in the company (Mallaby, 36-38). However, the passive financier eventually walked away with forty times more than the combined $2.4 million received by the eight founders. Rock believed he could do better for himself and for the founders...

The 1960s: The Emergence of Equity-only, Time-limited Venture Fund

From 1958 to 1968, the federal government formed the "Small Business Investment Company" program to subsidize startups with cheap loans and tax concessions (Mallaby, 41). However, the SBIC program ultimately failed to deliver on its promise of fueling startup growth due to a lack of oversight and accountability, as well as a focus on established businesses rather than truly innovative startups (Mallaby, 43).

Starting from 1961, Arthur Rock and Tommy Davis (with their investments made at Scientific Data Systems, Teledyne, and Intel) introduced the concept of equity-based, time-limited venture capital fund (Mallaby 44-55):

They seeded their first venture capital fund with $100,000 of their own money and raised an additional $3.2 million from a group of about thirty "limited" partners (LPs). The LPs were primarily wealthy individuals who acted as passive investors, including six of the eight founders of Fairchild Semiconductor.

For the first time in the history of finance, Davis & Rock compensated everyone in the fund, including limited and general partners, entrepreneurs, and key employees, with equity rather than cash.

By 1968, Davis & Rock earned returns of 233x and 22.6x respectively from investments at Scientific Data Systems (their initial $257,000 later became $60 million) and at Teledyne (their initial $3.4 million later became $77 million), with each limited partner walking away with almost $10 million.

Also in 1968, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, the last two of the eight traitors that founded but had not yet left Fairchild, called Arthur Rock to help raise money for their new company called Intel. The three of them bought a total of 500,000 shares for $1 each, while the outside investors kicked in $2.5 million for $5 per share, meaning that "they would control the same number of shares as the founders even though they had stumped up five times more cash" (Mallaby, 55).

The 1970s: The Emergence of Hands-on Activism and Stage-by-Stage Gradualism

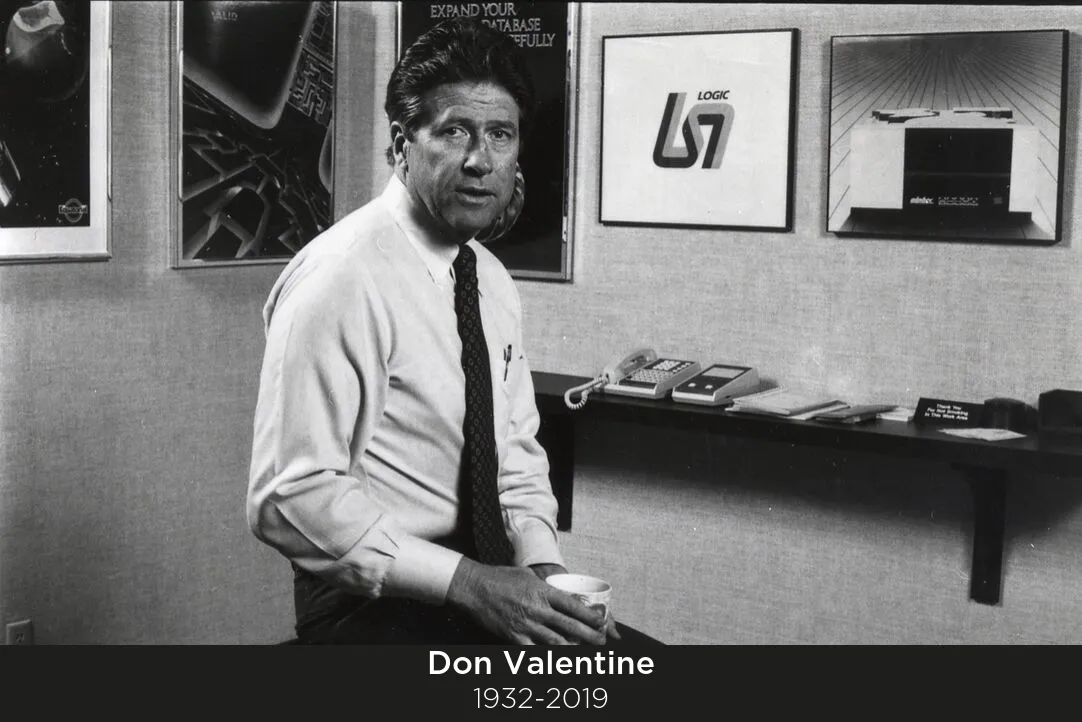

Don Valentine's Sequoia Capital and Tom Perkins's Kleiner Perkins became the leading VC figures in the Post-Arthur Rock era after their investment stories with Atari and Genentech (Mallaby, 61-92):

Don Valentine rose through the ranks till he became a sales executive at Fairchild Semiconductor after staying there for seven years and later joined National Semiconductor as its founding VP of Sales and Marketing. He also invested his own money in businesses, including SDS, the one investment that gave Davis & Rock a 233x return. In 1972, he founded Sequoia Capital:

In 1974, after failing to raise money from Wall Street bankers that looked down on him for not attending an Ivy League college or an elite business school, Rock managed to raise $5 million for his first Sequoia fund from the Ford Foundation and ironically from endowment funds of Yale, Vanderbilt, and Harvard.

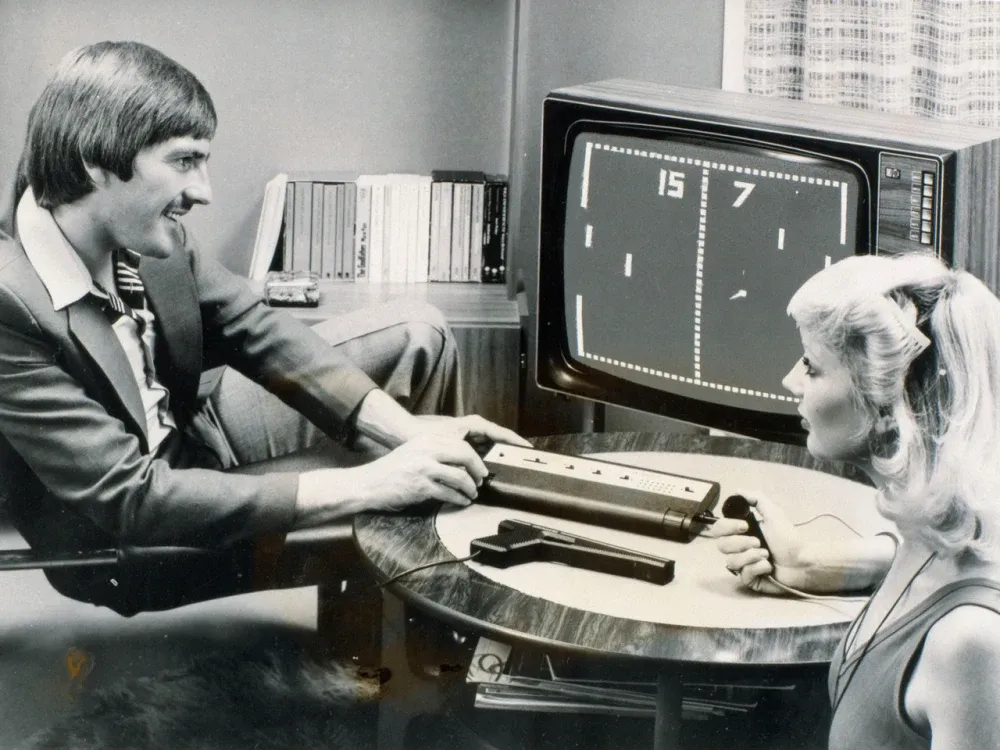

In 1975, Sequoia's first fund invested in Atari, the pioneering videogame company started by Nolan Bushnell. Throughout the investment, Valentine "invented" two innovative ways of investing:

Hands-On Activism: Before meeting Valentine, Bushnell only focused on selling his Pong video game to bars across the nation. But Valentine, as a hands-on business operator and a semiconductor salesman, learned how to "translate products into profits" and suggested that Atari's market size will expand enormously if they aim for selling Pong to families instead of bars.

Stage-by-Stage Gradualism: In late 1974, when Valentine first visited Atari's factory, he thought the company was too chaotic, but its potential was too terrific to walk away from. So he waited until Atari had a promising new product (the "Home Pong" machines that Valentine had pushed for) and a powerful distributor to invest his "seed" round money (62,500 shares for $62,500) by June 1975. Two months later, he made the next "Series A" investment by putting together more than $1 million to help Atari expand. But in late 1976, realizing that Atari would not be able to raise enough money for expanding, Valentine pushed Bushnell to sell Atari to a wealthy parent company for $28 million, a 3x return for Sequoia.

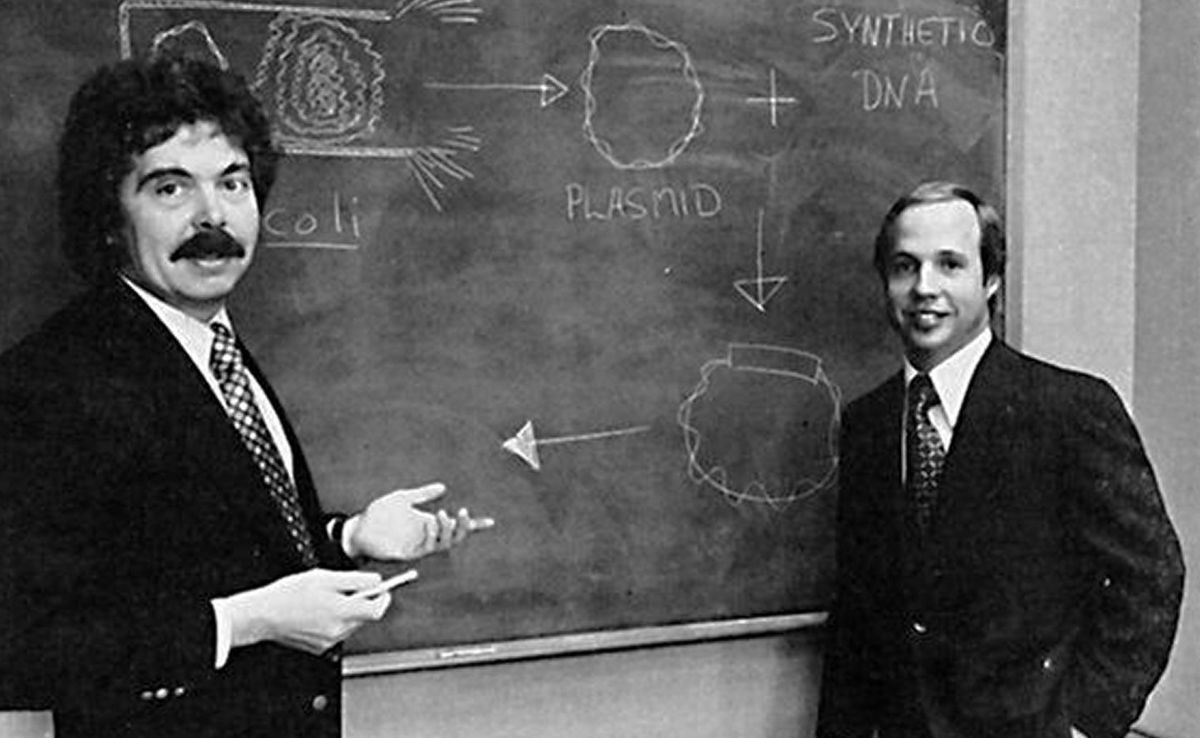

As Valentine founded Sequoia Capital, Tom Perkins and Eugene Kleiner also founded Sequoia's biggest rival, Kleiner Perkins, in 1972. They brought the concept of liberation capital, hands-on activism, and stage-by-stage gradualism to a new level when they helped launch the world's first biotechnology company, Genentech:

Smelling the Opportunity: Bob Swanson, who had been fired from Kleiner Perkins but still kept going to the office without pay, was impressed by recombinant DNA technology. He connected with Herbert Boyer, the co-inventor of the DNA technology, who eventually agreed to team up with Swanson and take KP's venture money.

Hands-On Activism: Perkins saw the potential for earning substantial profits from this technology due to formidable technical barriers to entry. He proposed cutting costs by not hiring scientists or setting up a lab and instead contracting early work to existing laboratories.

Stage-by-Stage Gradualism: In 1976, Perkins invested $100,000 for 25% of Genentech's stock. In 1977, he started a new financing round of $850,000 for 26% of Genentech, and in 1978, another financing round of $950,000 for 8.9% of Genentech was set up.

Bonanza Time: In 1980, Genentech went public, and Kleiner Perkins enjoyed a 200x return as the stock soared.

The early risk elimination combined with stage-by-stage financing techniques made Don Valentine and Tom Perkins the founding fathers of hands-on activist-style VC.

In 1978, Congress reduced the capital-gains tax from 49% to 28%, further spiraling more capital into VC funds and contributing to the blossoming and increasing competition of the entire VC industry for the next decade.

The 1980s: The Emergence of "Venture Network" and Specialist-Style VC

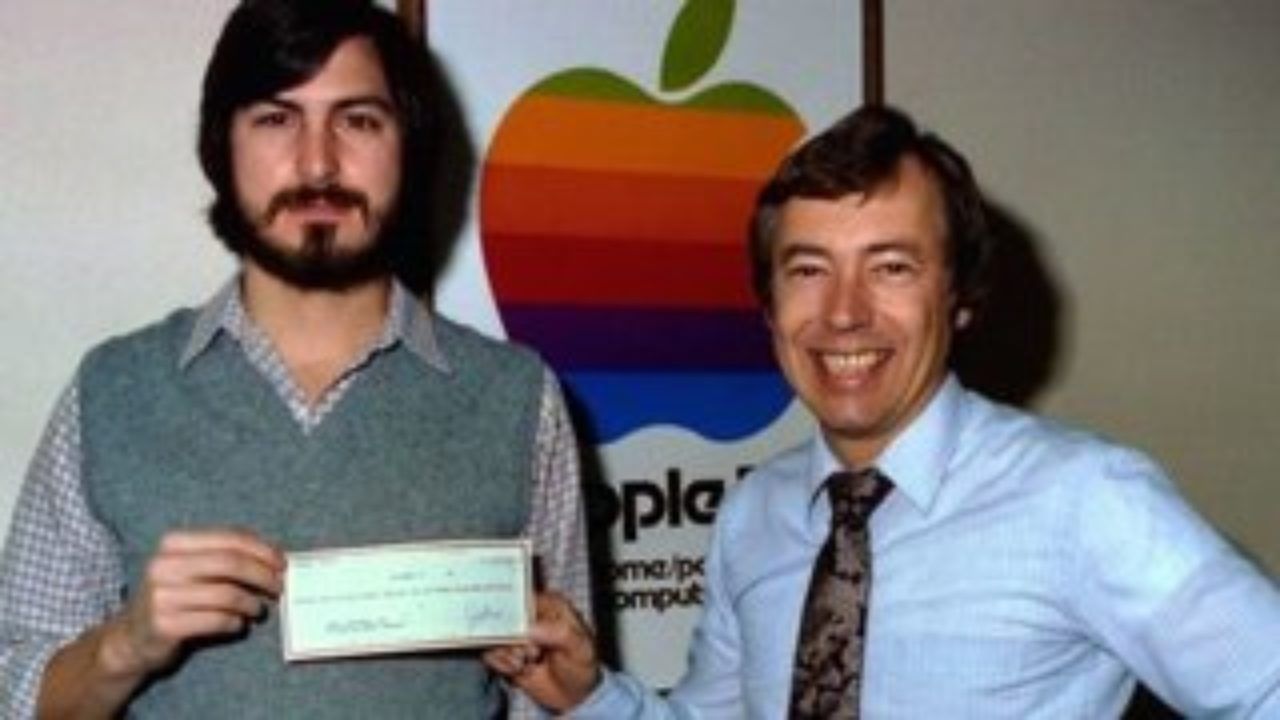

The emergence of the first venture network had everything to do with the financing story of Apple (Mallaby, 82-90):

Steven Jobs and Steve Wozniak founded Apple in 1976.

Jobs asked his ex-boss (from Atari) Nolan Bushnell to invest $50,000 for one-third of Apple.

Bushnell rejected the offer but introduced the Steves to Sequoia's Don Valentine (Atari's investor).

Valentine rejected to invest but introduced them to three managers who could help build Apple (while Tom Perkins and Eugene Kleiner, among other famous VCs, refused to even meet with Steve Jobs).

Mike Markkula (one of the three managers, who knew Valentine from working at Fairchild Semiconductor) was impressed by Wozniak's computer invention and invested $91,000 for 26% of Apple.

Markkula convinced his Fairchild alumnus Mike Scott to quit his job to be Apple's first president.

Markkula introduced Apple to another ex-Fairchild colleague Hank Smith.

Hank Smith, who now worked at Venrock (the Rockefeller family venture fund), introduced Apple to pitch in front of Venrock partners (one of the senior partners was Peter Crisp).

Venrock invested $300,000 for 10% of Apple in 1977 (without really listening to the pitch by Steve Jobs).

Markkula introduced Apple to Andrew Grove, his ex-colleague from Intel, who soon agreed to buy a small stake in Apple.

After investments from Venrock and Grove, Valentine started stalking Markkula and insisted that Sequoia wants a piece of Apple (though they didn't need any money from Valentine by then).

Arthur Rock initially refused to invest in Steve Jobs after Markkula's introduction, but after Regis McKenna (another connection from Markkula's valley network) whispered about Apple to Rock, Rock became interested.

Rock called Dick Kramlich (his ex-partner who replaced Tommy Davis) who knew Peter Crisp from Venrock (Rock previously had let Venrock into Intel's financing round in 1968, so Crisp owed Rock a favor).

Crisp then allowed $50,000 worth of Venrock's Apple allocation, which Kramlish would take $10,000 for himself and leave the rest of $40,000 to Rock.

Through Kramlich, Kramlich's British friend Anthony Montagu learned about Apple and asked Kramlich to call Apple's president Scott to meet with him. He then flew to California to beg Scott for allowing him to invest in Apple, but he was immediately rejected by Scott because they didn't need any extra money. However, a few hours after the rejection (Montagu was mentally prepared to live in the lobby of Apple's office building until Scott agreed to allow him to invest), Scott came down and brought Montagu the good news that Steve Wozniak just happened to want to sell $450,000 worth of his Apple equity to get a house.

To return his friend who introduced him to Apple a favor, Montagu called back Kramlich to split the allocation of Apple stock that he just bought from Steve Wozniak.

In December 1980, two months after Genetech's IPO, Apple went public. While Don Valentine made a quick 13x return on Apple by selling all his Apple stocks in 1979, Arthur Rock reaped a staggering 378x return by holding onto his Apple stocks for later. This story highlights how "the network could be stronger than the individual" (Mallaby, 90).

The Emergence of Specialists (Mallaby, 128 - 144)

In 1983, Arthur Patterson and Jim Swartz founded Accel Capital, the first venture fund that specialized in particular fields such as software and telecoms. Their specialist approach challenged the generalist approach adopted by traditional VCs like Sequoia and KP. Unlike the early Intel and Apple days when first investors would welcome co-investors, VCs by now would have to earn the opportunity to invest.

Being specialized in technologies would be more appealing to entrepreneurs who were innovating in those particular areas, and therefore, earning the opportunities to invest in them. The advantages of Accel's specialist approach can be demonstrated in their UUNET deal that eventually earned them a 54x return with a profit of $188 million (Mallaby, 144).

In 1986, despite skepticism shared among many Sequoia partners, Don Valentine welcomed Michael Moritz (a History major from Oxford University, a magazine journalist, and the author of two business books) to their team (Mallaby, 151). Valentine interviewed Moritz and recognized him as a hungry upstart and a versatile learner who could compensate for his lack of business or engineering background. Moritz set out to prove his value with his unconventional background in the following decade and eventually climbed up to the top rank of Sequoia.

The 1990s: The Emergence of Growth Investments and Angel Investments

The Introduction of Growth Investments - A Yahoo Story (Mallaby, 152-160):

In April 1995, Moritz led Sequoia to invest $975,000 in a small startup founded by two Stanford PhD students, David Filo and Jerry Yang, in exchange for 32% of its equity (Mallaby, 152). The startup was an internet-based website called Yahoo. While Moritz saw the potential of the internet, most traditional VCs at the time viewed Yahoo as just a cash-burning business that had to keep reinvesting revenues into marketing expenditures.

In late 1995, the VC world was about to change when Japanese-Korean investor Masayoshi Son entered the scene. After earning an Economics degree from UC Berkeley and making a fortune from his SoftBank startup, Son decided to invest as a non-traditional VC.

At a time when only the best VCs could raise a fund at the size of $250 million and split the risk by investing in dozens of startups, Son offered to put $100 million on one single bet: Yahoo.

When Moritz, Yang, and Filo were indecisive about whether to take Son's money or to go public with Goldman Sachs, Son played the "Godfather" card, saying, "If I don't invest in Yahoo, I'll invest in Excite (Yahoo's biggest rival at the time) and I'll kill you."

The Yahoo founders and Sequoia partners accepted Son's offer, knowing that his $100 million would be the determining factor in the winner-takes-all internet game.

In April 1996, Yahoo went public, and Son made an instant profit of more than $150 million.

In 1997, Son invested $100 million in GeoCities, a pioneering web-hosting company, and gained over $1 billion after it went public within a year of his investment.

In 1998, Son invested $400 million in online financial services company ETrade for 27% of its equity, which became $2.4 billion worth of stocks only after a year.

Between 1996 and 2000, Son gained up to $15 billion through growth investing and became the only VC billionaire at the time.

The Rise of Angel Investing - A Google Story (Mallaby, 174-178):

In August 1998, two Stanford PhD students, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, tried to raise money from Andy Bechtolsheim (cofounder of Sun Microsystems and founder of networking company Granite Systems) for their search company called Google.

Without asking many questions or analyzing the business potential of Google, Bechtolsheim wrote a check of $100,000 payable to "Google Inc." even though Brin and Page hadn't incorporated themselves yet.

By the end of 1998, the Googlers raised over $1 million from four angels, including Bechtolsheim, David Cheriton (a Stanford professor and Bechtolsheim's co-founder at Granite Systems), Ram Shriram (who got rich after selling his startup to Amazon), and Jeff Bezos (founder of Amazon).

By June 1999, Kleiner and Sequoia each bought 12.5% of Google equity for $12 million, as Google refused to sell any shares to either of them otherwise.

Since the Google deal, "the balance of power between entrepreneurs and VCs had shifted."

In 2000, the dot-com bubble burst due to excessive money in the VC and internet startup world, leading to the emergence of new investing approaches in the following decade.

The 2000s: The Emergence of Hands-off Investments and Batch-based Seed Investments

The Introduction of Hands-off Investment - A Facebook and SpaceX Story (Mallaby, 196 - 214):

In 2002, Peter Thiel, a Stanford graduate with a BA in philosophy and JD in law, made $55 million by investing, co-founding, and eventually selling PayPal to eBay.

In September 2004, Sean Parker and Mark Zuckerberg, co-founders of Facebook, sought private angel investors after rejecting offers from Google, Benchmark Capital, and Sequoia Capital. Reid Hoffman, the founder of LinkedIn, introduced them to his old buddy from Stanford and Paypal Peter Thiel, who angel-invested $500,000 for 10.2% of Facebook. Hoffman and another entrepreneur, Mark Pincus, also invested $38,000 each.

These angel investors adopted a hands-off approach, allowing the Facebook team to work independently without interference.

In 2005, Thiel launched Founders Fund (FF), a VC firm founded by successful entrepreneurs. At FF, Thiel introduced several innovative investment ideas:

Monopoly: Thiel believed that a startup that monopolized a worthwhile niche would capture more value than millions of undifferentiated competitors.

Hands-off Approach: Founders Fund rarely voted against a founder in a board vote and often did not take a board seat, contrasting the traditional hands-on approach.

Few, Big Bets: Thiel advocated for a small number of large, high-conviction bets instead of a wide spread of half-hearted ones.

Riskier, but Higher Potential: Thiel aimed for riskier, more innovative companies with world-changing potential. In 2008, Thiel invested $20 million in SpaceX for a 4% stake, which later became worth hundreds of millions.

The Introduction of Batch-based Seed Investments - A Y-Combinator Story (Mallaby, 215-221):

Paul Graham, a Cornell and Harvard graduate with degrees in philosophy and computer science, co-founded the software startup Viaweb and made a fortune.

In 2005, after giving a lecture at Harvard and being approached by young entrepreneurs for investment, Graham co-founded the "Summer Founders Program" with his girlfriend Jessica Livingston and two of his Viaweb co-founders, who collectively invested $200,000.

This program evolved into Y Combinator (YC), which selected 20 startups from 227 applicants for its first batch in April 2005. YC invested $6,000 for a 6% equity stake in each startup. Among the selected founders were Sam Altman, who later led YC and co-founded OpenAI with Elon Musk, and the co-founders of Reddit, Huffman and Ohanian.

As described by Sebastian Mallaby, Graham "was not just meeting entrepreneurs and piggybacking on their talent. He was recruiting teenage coders and creating entrepreneurship."

The 2010s: The Rise of Growth Equity

The 2010s witnessed the rise of growth equity, driven by major investments in tech giants. This period was marked by Yuri Milner's investment in Facebook, Tiger Global's investments in Chinese internet platforms, and a16z's investment in Skype (Mallaby, 273-298):

Yuri Milner and Facebook

Russian investor Yuri Milner, who had never set foot in Silicon Valley, recognized Facebook's potential better than most Silicon Valley insiders and gained fame for his $300 million investment in the company:

By early 2009, Facebook had already received investments from Peter Thiel, Accel, and Microsoft. The company was not seeking or accepting any additional funding. Nevertheless, Milner believed in Facebook's unrealized growth potential and flew from Russia to Palo Alto to meet with Facebook CFO Gideon Yu (and eventually Mark Zuckerberg himself). Milner made a few crucial points:

He argued that American VCs were wrong in thinking that Facebook, which had just reached 100 million users, had reached a saturation point. Milner had seen the growth of VKontakte, the Russian Facebook clone, and was convinced that Facebook's user base could continue to expand, especially since the site was not even among the top 5 websites in the U.S. at the time.

Milner noted that Facebook was not generating as much revenue per user as its international counterparts (Chinese social media platforms partially earned revenue from virtual gift-sending, and VKontakte's revenues per user were five times higher than Facebook's in 2009). This represented a significant opportunity.

To address Zuckerberg's strong control of Facebook, Milner promised not to take a single board seat, giving Zuckerberg as much freedom as possible.

In May 2009, Milner's investment company, Digital Sky Technologies (DST), purchased $200 million worth of company-issued primary stock for a 1.96% stake in Facebook, giving Zuckerberg the $10 billion pre-money valuation he wanted. DST then bought over $100 million worth of secondary employee stock, allowing employees to cash out and purchase homes and cars after being "stock option millionaires" for years.

Bonanza Time: By late 2010, within 18 months, Facebook's valuation had soared from $8.6 billion to $50 billion. This resulted in a profit of more than $1.5 billion for DST, reminiscent of Masayoshi Son's $100 million bet on Yahoo 13 years earlier.

Tiger Global and the "This of That" Strategy

Chase Coleman and Scott Shleifer of Tiger Global gained prominence for their "this of that" strategy, which involved investing in companies that resembled successful American companies but operated in emerging markets. Their approach focused on incremental margins instead of profit margins, allowing them to identify potential growth opportunities that others might have overlooked.

As early as 2003, Yuri Milner began building Mail.ru, often referred to as the "Yahoo of Russia," and established contact with Shleifer. In early 2004, recognizing the potential growth of the Russian market, Tiger Global invested in Mail.ru, Rambler (Mail.ru's rival), and Yandex (the "Google of Russia"). In 2005, Shleifer expanded his search for "this of that" opportunities to Latin America.

The connection between Yuri Milner and Tiger Global deepened as they started co-investing in several tech companies around the world. Some notable examples include:

JD.com (China): Often called the "Amazon of China," JD.com is a major e-commerce platform in China. Both Yuri Milner's DST and Tiger Global recognized JD.com's potential early on and invested in the company in between 2011 and 2014, which has since become one of the largest e-commerce platforms in China, rivaling Alibaba.

Flipkart (India): Referred to as the "Amazon of India," Flipkart is an Indian e-commerce company founded in 2007. Tiger Global first invested in Flipkart in 2010 during the company's Series B funding round. DST joined later, investing in Flipkart in 2014 during the company's Series G funding round. Their investment proved lucrative when Walmart acquired a majority stake in the company in 2018 for $16 billion.

Mail.ru (Russia): Known as the "Google of Russia," Mail.ru is a Russian internet company that offers various services such as search, email, and social networking. Both DST and Tiger Global invested in Mail.ru, which has grown to become one of the largest internet companies in Russia.

Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) and the Skype Story

Andreessen Horowitz, or 'a16z', co-founded by Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, combined the faith in scientific founders with the toughness of Don Valentine.

Founders: a16z was co-founded by Marc Andreessen (co-founder of Netscape) and Ben Horowitz (early Netscape employee).

eBay's Acquisition of Skype: In 2005, eBay acquired the telephony company Skype but struggled to make it profitable. Skype's Swedish founders were fired by eBay and sued over the ownership of Skype's core technology.

Andreesen's Deal: As an eBay board member, Andreesen proposed a deal to bring Skype's founders back by letting Silver Lake private-equity group buy more than half of Skype's stock, leaving 14% to the founders if they dropped their lawsuits. The deal also allowed a16z to invest.

a16z's Investment in Skype: In September 2009, a16z invested $50 million in Skype, which had been acquired by eBay four years earlier.

Management Overhaul and Alliance with Facebook: To fix Skype's management problems, 29 of the 30 top managers were replaced. Andreesen then leveraged his connections to forge an alliance between Skype and Facebook, enabling Facebook users to call each other over Skype's video connections. This cloud transition was facilitated by Skype's strong technical team, in which a16z had faith.

Microsoft's Acquisition of Skype: In 2010, Microsoft purchased Skype for $8.5 billion, earning a16z a profit of $100 million.

Venture investing in the 2010s demonstrated the importance of making bold, binary decisions based on messy information, accepting the reality of being frequently wrong, and reaping huge rewards when right (Mallaby, 250).

Today: The Complete Venture Capital Industry

The venture capital landscape has evolved significantly over the years, with the emergence of avuncular angels, factory-batch incubators, entrepreneur-centric early-stage sponsors, and data-driven growth investors (Mallaby, 303). This diverse ecosystem of investors and innovators has not only enabled startups to access a broader range of funding options but has also fostered a supportive environment for entrepreneurs to grow their businesses.

In today's interconnected and rapidly changing world, the venture capital industry continues to play a crucial role in driving innovation, creating jobs, and shaping the future. The success stories of companies backed by visionary investors and firms like Arthur Rock, Don Valentine with his Sequoia Capital, Tom Perkins with Kleiner Perkins (KP), as well as those supported by Yuri Milner and Tiger Global, demonstrate the transformative power of venture capital and its ability to turn groundbreaking ideas into world-changing businesses.

As we move forward, the venture capital industry will undoubtedly continue to evolve, responding to new challenges and opportunities in the global market. One thing is certain: venture capital will remain an essential force in fostering innovation and enabling entrepreneurs to bring their visions to life.

Reference:

Mallaby, Sebastian. The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Art of Disruption. Allen Lane, 2022.

(Everything discussed above comes from my recent reading The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Art of Disruption by Sebastian Mallaby. Strongly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in finance or startups.)

Thanks to Myles Zhou for reading drafts of this.